Award-winning chemistry lecturer Michael Seery shares his experiences combining technology and the classroom

I was privileged to have the honour of being awarded the 2012 Royal Society of Chemistry Higher Education Teaching Award. One of the benefits of receiving this award is a supported lecture tour, enabling me to talk about my use of technology in chemistry teaching at five UK universities. In my final duty before passing the title to this year’s award winner, Simon Lancaster, I have written a synopsis of that lecture below.

What I learnt

Chemistry is sometimes criticised for being too traditional in its approach to teaching, but from the conversations I had while visiting these five institutions it is evident that an enormous amount of innovative practice is becoming ever more embedded in our teaching and learning activities. At Keele University, the first year laboratory programme had been reorganised, so that there was a progressive development of all laboratory-related skills over the year, along with a full practical exam at the end of the year. Lab assessment was also being reconsidered at Imperial College London, where staff had introduced a range of innovative peer assessments of samples and spectra, facilitated by an academic staff member. Staff at Kingston University were trialling PeerWise, an online repository of multiple-choice questions that are created, answered, rated and discussed by students.1 At the University of Leicester, an interesting science communication project had become so popular that it was intended that it become a core module. Newcastle University is running an impressive outreach programme where MChem students are collaborating with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre in the development of A-level study sheets.

Using technology

The mantra often quoted when thinking about choosing technology to assist our teaching is ‘pedagogy before technology’. I learnt this the hard way, as naive enthusiasm led to the development of resources that were made because they could be made, and now linger somewhere in a virtual graveyard. Mature reflection has led me to be much more critical when considering whether to invest valuable time into the incorporation of some element of technology into teaching. Something that looks great with lots of buttons to press will be of little use if it is not embedded in curriculum delivery, and addresses a particular teaching need. A simple resource that covers a topic students find difficult or addresses an area of curriculum delivery that can be troublesome is likely to be much more useful to students.

Following on from this, a resource that we feel is important in our curriculum delivery should be intimately linked with our in-class delivery. This can be done by considering how we relate it to our in-class work; when the students are meant to interact with it; and how we will know whether they have. Attributing it this importance gives it a sense of value to the students, and it is more likely to become embedded in the overall curriculum delivery, so genuinely blending the in-class teaching with the online resource.

Preparing for lectures

The first concept to discuss under this framework is pre-lecture activities, which were described in a previous issue of Education in Chemistry.2 That article explains the theoretical rationale of these resources in the context of cognitive load theory. Briefly, these resources were used to address a gap in student performance that correlated with the extent of their prior knowledge.3 Therefore the rationale was that in order to address this gap, I would bring in pre-lecture activities to introduce some core concepts to students in advance of the lecture. This is essentially the same idea as giving students some pre-lecture reading, but by wrapping it up in a video that the students watch prior to the lecture, it is easy to see whether students are using it. Including a simple quiz enables students to get value out of the resource by gaining some feedback, and also gives the lecturer a general impression of how well students understood the material. Technology facilitates the automation of all of this, so after initial set-up, they require little on-going effort. The pre-lecture work is blended into the lecture itself by building on the concepts introduced in advance, thus attributing them that important sense of value.

In my own work, I have found that using pre-lecture activities removed the correlation between prior knowledge and academic performance in my first year chemistry module.4

A place to talk

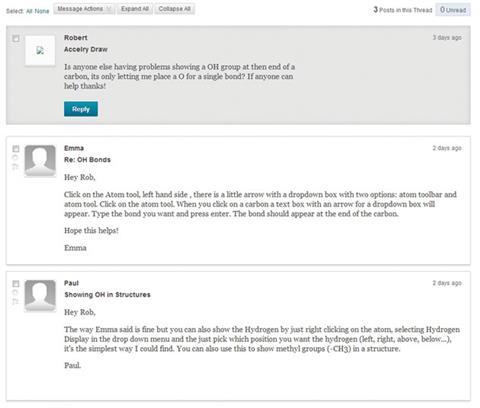

Discussion boards are the equivalent of an online noticeboard where a query or statement can be posted, and replied to by several people. While they are included in most virtual learning environments, their usage is usually restricted to supporting modules that are delivered entirely online. My own use of discussion boards originated here, where they were used as a space for students to pose questions, interact with each other, and gain general feedback for a module delivered online.5

After seeing there how useful they could be for students, I decided to include them in some in-class modules. The rationale for this was that discussion boards can act as a useful space to work through any concepts causing difficulties, but in a manner that students can interact with in their own time and at their own pace.

A very basic level of discussion board usage is as a question and answer space, where lecturers can answer queries as they arise. This in itself is useful, as it avoids answering individual emails of commonly asked questions. Developing on these queries in the lecture room can demonstrate that it is worthwhile to students to make the leap and post their queries, and again strengthens the link between in-class and online work.

Another aspect that is useful is to structure the approach to study. A series of posts over the module outlining what progress has been made and what the student should be doing at various stages can help scaffold the revision process, especially for students new to higher education.

However, it is as a space where students can interact with their peers that discussion boards have great potential. The process of explaining a topic to each other is a great way for students to develop their writing skills, their chemistry knowledge, and their online etiquette. By explaining and writing, students have to have a clear sense of the topic they are discussing, and the process of writing helps them clarify their own understanding. Online etiquette (netiquette) is not commonly a feature of undergraduate programmes, but it is an important skill to develop as more and more professional work moves online. This can be developed in the first instance by the lecturer leading by example, and I aim to adopt a professional but friendly tone in discussion posts, with full sentences and correct grammar. Setting such a tone, and gently enforcing it means that the space becomes a space where students are acting as chemists discussing chemistry in a professional (but friendly) environment.

Perhaps the greatest barrier to the adoption of discussion boards in a blended learning environment is the reluctance of students to post. Some tips have emerged from the literature and my own practice over the years.6 To familiarise students with discussion boards, I usually ask them to post a question about a chemistry topic, and reply to another question. This ensures that they can complete the physical act of posting, but also breaks the barrier of making the first post. To prompt student queries, a lecturer’s post could illustrate an answer to a question using a worked example, or an incomplete answer, and then ask a similar question or follow-up questions. Another option is to model the process of asking a question and response, by posting an example query and the response that would be given. A good way for students to test their understanding of a topic is to see if they can use it in a more involved, open-ended problem, and follow-up questions could probe this, or structure student’s approach to it. It may be that a discussion board is used for a part of a module that causes particular difficulty, so the usage and attention it needs is focused over a shorter period of time.

It’s important to state though that a student who is reading other posts but not posting their own is still learning. I don’t identify ‘lurkers’ publicly but tend to encourage them out by occasionally summarising what has been contributed, and requesting other opinions or thoughts. Hopefully, those who are shy about posting will eventually feel they can, but as with an in-class scenario, there will always be some who won’t.

More involved work on the part of students, such as more extensive writing and peer-review, will realistically require some assessment. Following on from the initial argument, the process here is to look at what is required from this aspect of curriculum delivery. If it is writing and reviewing, then the assessment might look at students written answers in explaining a topic, and their assistance with another student’s piece. This keeps the assessment to a manageable level. While discussion boards do take work, achieving genuine peer interaction through writing and responding is a very powerful learning exercise, and one difficult to achieve elsewhere.

Wikis

A wiki is an online document editing space that several users can access. It has the advantage that the latest version of the document is always available to everyone. The editing is traceable, so all contributors (and the assessor) can see who adds what, and when. This makes it an excellent tool for managing group assignments, as the process is transparent, and obvious to students that it is so.

My rationale for introducing wikis into my curriculum was that I taught an advanced materials analysis module that was difficult to assess in a traditional exam. The final year module focused on discussing several thermal and surface analysis techniques, and selecting appropriate techniques for various sample types. Students were broken into groups, and each group had to work collaboratively on their assignment. The work involved explaining the instrumentation used in the techniques they chose, sourcing sample results from the literature, explaining how results could be compared and contrasted, and writing the entire document to a professional standard. I found that because the students were aware of the traceability of the wiki, they tended to add their contributions regularly, and periodic formative feedback components kept them on track.

It is interesting to compare this means of assessment with the traditional exam. In using this assessment, several additional learning outcomes are achieved: students have to work in groups, source information, justify choices, explain scientific processes and write to a professional standard. Many of the final pieces produced were of a very high standard. Assessing the work by examination alone, I found that students usually reverted to the ‘learn and repeat’ method, leaving little room for independent thought and flair. The wiki’s traceability and work process also makes it ideal to make available to external examiners.

Conclusions

Our approach to incorporating technology in education is maturing to a stage where the integration of technology into curriculum design is becoming mainstream. By addressing the series of questions ‘why should I spend time making this resource/facilitating this activity?’, ‘what will students achieve from using this resource/activity?’ and ‘how will I know if they have?’, a lecturer can determine what value the inclusion of a particular technology really has in their curriculum. These are more likely to have greater uptake and be more useful to student learning.

There is a lot of information available now about the use of technology in chemistry education, not least from the Royal Society of Chemistry. Over the last two years, Education in Chemistry has published several articles on including technology in the curriculum, on topics such as PeerWise, screencasting, flipping lectures and more. A themed issue of the RSC’s free-to-access journal Chemistry Education Research and Practice on the Application of Technology to Enhance Chemistry Education, guest edited by my colleague Claire Mc Donnell and I, was published in August this year. This contains several articles on the innovative use of technology in chemistry teaching, and gives plenty of ideas and inspiration for those wishing to embed some technology in their teaching.7

Michael Seery is a lecturer in physical chemistry at the Dublin Institute of Technology, Ireland

Acknowledgements

My thanks go to the RSC Education Division for supporting my lecture tour and the hosts in the institutions for their hospitality and conversation.

References

- Student-generated assessment, Education in Chemistry, January 2013, p18

- Jump-starting lectures, Education in Chemistry, September 2012, p22

- M K Seery, Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2009, 10, 227 (DOI: 10.1039/B914502H)

- M K Seery and R Donnelly, Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2012, 43, 667 (DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-8535.2011.01237.x)

- M K Seery, Chem. Educ. Res. Pract., 2012, 13, 39 (DOI: 10.1039/C1RP90059E)

- G Salmon, E-moderating: the key to teaching and learning online. Routledge, 2004; J Markwell, Biochem. Mol. Biol. Educ., 2005, 33, 260 (DOI: 10.1002/bmb.2005.49403304260)

- http://rsc.li/1faBtCj

No comments yet