The consumption of absinthe was once banned due to its reputation as a mysterious psychoactive drink. What does it contain? Was it responsible for the death of Van Gogh?

- Absinthe contains a number of different terpene and terpenoid molcules

- The consumption of absinthe was just one of several factors in Van Gogh's lifestyle which could have caused his illnesses

Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) was a pioneer expressionist artist. Working as a painter for only the last 10 years of his life, much of his best-known output occurred in the last two years, after he encountered impressionism.

Before committing suicide, he spent a long period in 1889-90 in a clinic because of his mental instability. Just look at his paintings such as La Nuit Etoilée in a gallery like the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and you do not have to be a chemist to wonder about the source of the swirls, spirals and other strange effects.

Traditionally Van Gogh's instability and suicide have been blamed on the liqueur-like drink absinthe, the fashionable French beverage in the half century up to the first world war. But was absinthe really to blame?

The green fairy

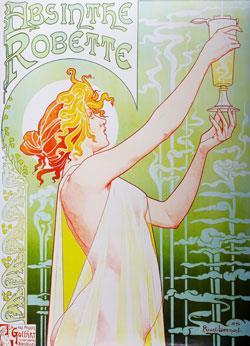

Absinthe, a green liquid with an anise smell, is made by distilling a mixture of alcohol, herbs (notably wormwood) and water. It became a national drink in France in the late 19th century. Fashionable among the artistic community, it became cheap enough to be the drink of choice among the poor.

Writers such as Baudelaire, Edgar Allan Poe and Verlaine relied upon it, and a whole range of artists are associated with it, often for including it in their paintings, such as Degas, Gauguin, Manet, Picasso, Toulouse-Lautrec, and of course Van Gogh. Known as la fée verte (the green fairy), absinthe gave rise to l'heure verte, the time (5 pm) when drinkers of all sorts went to a café for their absinthe, what we would now call a 'Happy Hour'.

Drinking absinthe was a stylised activity.1 First a shot of the liqueur was added to a glass and a slotted absinthe spoon was placed on top of the glass, with a sugar cube on top of that. Sugar offset the bitter taste of the wormwood in the neat absinthe. Ice-cold water was dripped onto the cube, the sugar dissolved, and the solution dripped into the absinthe. The drink would go cloudy, with a yellow opalescence, known as the louche effect.

Absinthe contains terpene and terpenoid molecules with large hydrophobic rings and chains; these are soluble in ethanol-rich absinthe, but insoluble in the more polar water-absinthe mixtures.

Terpenes

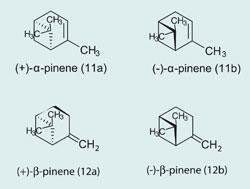

Terpenes are hydrocarbons produced mainly by plants and some insects. Familiar examples are pinene and limonene. Their molecular formula is (C5H8)n and they can be regarded as oligomers of isoprene, 2-methyl-1,3-butadiene, CH2=C(CH3)CH=CH2.

The great German organic chemist Otto Wallach was one of the pioneers of terpene chemistry. He was awarded the 1910 Nobel prize for chemistry, for devising the isoprene rule amongst other things.

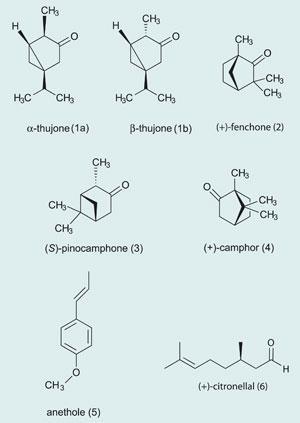

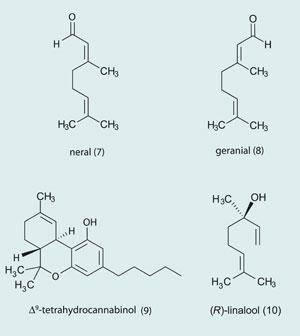

Oxidation of terpenes leads to alcohols, aldehydes and ketones, collectively known as terpenoids which also occur widely in nature (though occasionally, for convenience, they are referred to as terpenes too). Examples of terpenoids are menthol, camphor, thujone and geraniol.

When plants synthesise terpenes and terpenoids, they usually make just the one isomer. So the fennel plant makes d(+)-fenchone (2), the camphor tree d(+)-camphor (4) , and lavender and laurel both make R-(-)-linalool (10). Both α- and β-pinene (11, 12) exist as two enantiomers; with 1S,5S-(-)- α-pinene (11a) in European pines and 1R,5R-(+)- α-pinene (11b) in North America.

How absinthe is made

It is often stated, incorrectly, that absinthe was first concocted around 1792 by Pierre Ordinaire, a French emigrant to the village of Couvet in Western Switzerland, close to the French border.2 He created an elixir made by distilling a mixture of alcohol, herbs and water.

It seems that a drink of this type had been devised a long while before 1790; in 1797 the formula was bought by Henri Dubied, a Frenchman, who set up the first absinthe distillery in Couvet.3 In 1805, together with his sons and son-in-law Henri-Louis Pernod, Dubied opened a distillery at Pontarlier just over the French border (to avoid paying import taxes) under the company name of Maison Pernod Fils. The name Pernod came to be associated with absinthe.

A recipe of 1794 lists4 a large bucket of common wormwood (Artemisia absinthium), some mint, two handfuls of lemon balm, two of green anise, the same amount of fennel and some calamus. These would be macerated with brandy; water was added, and the mixture distilled. More herbs (Roman wormwood (Artemisia pontica), hyssop) are then added, chlorophyll is extracted giving the liquid its green colour, and water added to give the desired dilution (around 50-75% alcohol).

Compounds from the herbs supplied flavourings, such as thujone (1) from wormwood, fenchone (2) from fennel, pinocamphone (3) and camphor (4) from hyssop, anethole (5) from anise, citronellal (6) and citral (a mixture of the isomers neral (7) and geranial (8)) from lemon balm.

The rise of absinthe

French troops in the Algerian wars of the 1840s were given absinthe to kill microbes and swore by it as good for fighting fevers like malaria. Its use continued to spread, and was given impetus by the outbreak of the phylloxera louse in the 1860s, which destroyed a majority of French vineyards. A further factor was that industrial alcohol came to be used to make absinthe, making it cheaper than wine and thus the most economical way for ordinary French people to get alcohol.5 Compared with wine's 8-10% ethanol content, absinthe had 50-70%.

As absinthe drinking spread in the second half of the 19th century, so did associated health problems. Doctors described symptoms such as addiction, fits, hallucinations (both auditory and visual) and delirium. These were associated with a complaint called 'absinthism', promulgated particularly by Dr Valentin Magnan, a highly-regarded physician.6 Not only did this come to be regarded as a syndrome quite separate from alcoholism, but wormwood and in particular one component, thujone, became regarded as its cause.

Magnan seized on the convulsive effects of neat oil of wormwood and transferred them to absinthe, which contained a very low level of it. Results of animal tests on dogs were extrapolated to apply to humans, and the toxicity of substances present in other herbs was ignored. In fact, the thujone content of wormwoods varies widely, with some wormwoods containing no detectable thujone.7 Recent studies by Luauté et al, show there is no epidemiological evidence for absinthism being different to alcoholism.8

The quality of absinthe was variable. Some manufacturers of inferior blends may have used copper salts like copper acetate, as a cheap (and toxic) way of getting the green colour,9 and other herbs like tansy may have contributed toxic compounds. Low-grade alcohol may also have been used, resulting in the presence of toxic alcohols like methanol.

As absinthe became more popular, it made two enemies. One was an increasingly vocal anti-alcohol lobby, who wanted alcoholic drinks prohibited (as in fact happened in the United States of America from 1920 to 1933); the second enemy was the wine makers, who saw their market vanishing. The impetus for a ban on absinthe came from Commugny in Switzerland.

On 28 August 1905, a Swiss peasant named Jean Lanfray came home from work and found that his pregnant wife had not waxed his boots while he was at work; after an argument, he shot her and their two daughters, aged two and four. The crime was blamed on the two glasses of absinthe he had drunk that day, ignoring the fact that he was an alcoholic who habitually drank 5 litres of wine a day, as well as spirits.

Lanfray's defence lawyer argued that he was in 'a state of absinthe-induced delirium' and therefore could not be held responsible for the crime. Found guilty, his sentence was one of life imprisonment but a few days later he committed suicide by hanging himself.

A rather hysterical reaction set in. Switzerland banned absinthe in 1908 and a domino effect led to bans in other parts of Europe (eg Netherlands, Italy) and the US. Its sale was forbidden in France on 16 August 1914, by Louis Malvy, the Minister of the Interior, since it was thought alcohol was weakening the French war effort.

A law banning the production, circulation and sale of absinthe was approved by France's Chamber of Deputies (422 for a ban, 58 against) on 4 March 1915, and became effective on 16 March 1915. It is only since 1988 that European Union legalisation has allowed the manufacture and consumption of absinthe with a limit of 35 mg l-1 of thujone.

The science of absinthe

The distinguished terpene chemist Friedrich Semmler reported10 the structure of thujone (1) in 1900. In 1902 Otto Wallach showed11 that 'absinthol' from wormwood was identical with 'tanacetone' in tansy oil and thujone in thuja oil. It was shortly after these discoveries were reported that thujone was claimed to be the toxic ingredient responsible for the health problems associated with absinthe, very likely because it was the only component to have been identified. It seems that absinthe and thujone were made the culprits for large-scale alcoholism.

It was not until scientists started looking at psychedelic drugs that thujone's properties were seriously investigated. In 1975, it was suggested that thujone was similar in structure to tetrahydrocannabinol (THC, (9)), the active ingredient of cannabis, and it was speculated that thujone might act on cannabinoid receptors in the brain.12 Tests, however, showed that thujone had only a very low affinity for cannabinoid receptors; moreover, rats administered thujone behaved differently to those given a cannabinoid agonist.13

Tests on α-thujone (more toxic than β-thujone) revealed that it modulated the GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid) receptor and that its metabolism resulted in the formation of less toxic metabolites.14

A claim had been made15 that absinthe from the era before its ban could contain up to 260 mg l-1 of thujone, much higher than that allowed under current legislation, and this has now been thoroughly tested. Synthetic absinthe made following three traditional 19th century recipes was found to contain at most 4.3 mg l-1 of thujones.16

GC-MS analyses of 17 present-day commercial absinthe samples indicated several contained little or no -thujone, four containing none. The highest level of α-thujone17 was only 33.3 mg l-1, though many samples had very high levels of anethole. An 'unknown' compound with a very similar retention time to α-thujone was identified as linalool (10); its misidentification in analyses could have led to high analytical values for 'thujone'.

Analysis of a vintage absinthe from 1930 showed only 1.3 mg l-1 for α- and β-thujone combined, and in another study 13 samples of authentic pre-ban absinthe were analysed, showing total concentrations of thujone within a range of 0.5 to 48.3 mg l-1, with an average value of 25.4 mg l-1. Fenchone and pinocamphone concentrations were also below toxic limits. The analysts also showed that these absinthes had been manufactured with very clean alcohol.18

Further analyses19 of 8 more pre-ban absinthes gave total thujone concentrations between 17.1 and 47.0 mg l-1.

One obvious challenge to these results would be to question the stability of thujone when kept for around 100 years, so subsequent research examined the effect of UV-irradiation upon absinthe samples. This revealed that if they were kept in clear glass bottles, there was a 18% reduction in thujone content after 200 hours irradiation, but if the absinthe was in the traditional green bottles, there was no deterioration. Reanalysis of samples first examined in 2001-5 also showed no deterioration.19

As already noted, since 1988 EU legalisation has allowed the manufacture and consumption of absinthe once more, and many brands are on the market, with names that include La Fée Absinthe, Century, Lucid, Kübler and La Clandestine Absinthe. Certain manufacturers of absinthe propagate the thujone myth, in order to promote their products to people who want to believe that absinthe must be dangerous.

So, what of Van Gogh?

It has been claimed that over a 100 different diagnoses of Van Gogh's illness have been made, including suggestions of an epilepsy-related illness20 and of a manic-depressive illness.21

Van Gogh appears to have suffered from pica, a compulsive eating of non-nutritional materials. Artists in those days used lead compounds for several bright colours - red lead Pb3O4 for red or orange; PbCrO4 as chrome yellow; and basic lead carbonate, 2PbCO3.Pb(OH)2 for white.

Caravaggio's instability and early death have recently been attributed to lead poisoning, judging by high lead levels in what are believed to be his bones.22 It has been pointed out that using heavy metal paints probably contributed to the rheumatoid arthritis23 suffered by artists like Renoir, Rubens and Dufy, whilst Weissman has suggested that Van Gogh's suicide may have been precipitated by plumbism, chronic lead poisoning.24

Though absinthe did indeed contain the terpenoid thujone, it also contained other compounds of this family, for which Van Gogh seems to have had a liking. On one occasion a fellow artist, Paul Signac, had to stop Van Gogh from drinking turpentine, in which the most abundant terpenes are α- and β-pinene (11, 12), whilst Van Gogh placed large amounts of camphor (4) in his pillow and mattress to combat insomnia.

An American doctor and professor, Wilfred Arnold, has made a detailed study of Van Gogh for many years, considering all the data from van Gogh's letters and other documents, and believes that acute intermittent porphyria (AIP) is the diagnosis that best fits the facts.25

Van Gogh's neurological problems could occur intermittently, flare up, and then subside rapidly. His lifestyle, involving poor diet, abuse of alcohol, smoking and pica for chemicals, was not conducive to good health.

AIP is caused by low levels of the enzyme porphobilinogen deaminase (involved in the synthesis of haemoglobin), usually inherited from an abnormal gene from a parent; this does not usually present problems as the normal gene from the other parent enables normal haem synthesis to occur.

Most people with a deficiency of porphobilinogen deaminase never develop problems, but attacks of AIP, with associated symptoms such as vomiting, diarrhoea, pains in the back and abdomen, physical weakness and mental problems, can be brought on by factors including drugs, slimming diets, alcohol and solvent abuse, as well as stress.

Absinthe was just one of several factors in Van Gogh's lifestyle which could have been precipitating factors for acute intermittent porphyria.

In conclusion

Van Gogh's art is truly remarkable, the fruit of his creative ability. In the words25 of Arnold,

He was a genius in spite of his illness - not because of it.

Further Reading

- J Adams, Hideous Absinthe. A History of the Devil in a Bottle. London: I B Tauris, 2004

- W N Arnold, J. Hist Neurosci., 2004, 13, 22

- W N Arnold, Vincent Van Gogh: Chemicals, Crises and Creativity. Berlin: Birkhauser, 1992

- B Conrad, Absinthe. History in a Bottle . San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1988

- D Lanier, Absinthe. The Cocaine of the Nineteenth Century. Jefferson NC: McFarland, 1995

- J Mann, Turn On and Tune In, Psychedelics, Narcotics and Euphoriants, pp 123-135. Cambridge: RSC Publishing, 2009

- S A Padosch et al, Subst. Abuse. Treat. Prev. Policy, 2006, 1, 14 (DOI: 10.1186/1747-597X-1-14)

- C S Sell, A Fragrant Introduction to Terpenoid Chemistry. Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry, 2003

References

- J Adams, Hideous Absinthe. A History of the Devil in a Bottle, pp 66-68. London: I B Tauris, 2004

- J Adams, Hideous Absinthe. A History of the Devil in a Bottle, pp 20-21. London, I B Tauris, 2004

- B Conrad, Absinthe. History in a Bottle, pp 88-89. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1988

- D W Lachenmeier et al, Open Addict. J., 2010,3, 32

- M Huisman et al, Int. J. Epidemiol., 2007, 36, 738

- D W Lachenmeier and D. Nathan-Maister, Dtsch. Lebensm.-Rundsch., 2007, 103, 255

- F Chialva et al, Z. Lebensm. Unters. Forsch., 1983, 176, 363

- J P Luauté, Evol. Psychiatr., 2007, 72, 515

- W N Arnold, Vincent Van Gogh: Chemicals, Crises and Creativity, p 115. Berlin: Birkhauser, 1992

- F Semmler, Ber. der Deutsch. Chem. Gesellschaft, 1900, 33, 275

- O Wallach, Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem., 1902, 323

- J del Castillo et al, Nature (London, UK), 1975, 253, 365

- J P Meschler and A C Howlett, Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav., 1999, 62, 473

- K M Höld et al, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 2000, 97, 3826

- J Strand et al, Br. Med. J., 1999, 319, 1590

- D W Lachenmeier et al, Forensic Sci. Internat., 2006, 158, 1#

- J Emmert et al, Dtsch. Lebensm.-Rundsch, 2004, 100, 352

- D W Lachenmeier et al, J. Agric. Food Chem., 2008, 56

- D W Lachenmeier et al, J. Agric. Food Chem., 2009, 57, 2782

- D Blumer, Am. J. Psychiatry, 2002, 159, 519

- K R Jamison, Touched with Fire: Manic-depressive Illness and the Artistic Temperament. New York: The Free Press, 1991

- Tom Kington, The mystery of Caravaggio's death solved at last - painting killed him, The Guardian, 16 June 2010

- L M Pederson and H Permin, Lancet, 1988, 331, 1267

- E Weissman, J. Med. Biog., 2008, 16, 109

- W N Arnold, J. Hist Neurosci., 2004, 13, 22

No comments yet