Five smart tips to help your students understand the topic and answer exam questions successfully

Rate of reaction and equilibrium may seem like very different topics to students. Depending on how a curriculum is organised, they may occupy quite different teaching slots. Rates are fairly intuitive and so this topic often comes earlier in students’ chemistry education, with equilibrium seeming much more abstract and therefore left until later. However, the yield obtained from a reaction is always a function of the synergy between the position of equilibrium (how far) and the rate of reaction (how fast).

For students in their exam years, questions which rely on an evaluation of both rate and equilibrium are often used to discriminate between the best candidates. They can seem daunting, but can be made accessible to all students with some careful planning.

1. Explore their prior knowledge

The concept of a reversible reaction seems to come out of the blue. Throughout their chemical education so far, students will have seen arrows that only go in one direction. They may be strongly attached to the idea that chemical change is irreversible (in contrast to physical change). Even though in the calculations topic students may have had to calculate percentage yield using theoretical yield, they often still think that a reaction goes 100% from start to finish. Explore this before moving onto ideas about reversible reactions. After all, their knowledge isn’t wrong, it’s just working with a simpler model. Discussing this explicitly helps students to put aside their simpler models and develop their thinking into more difficult concepts.

Check students have a working knowledge of both topics before beginning questions which bring them together. Provide one-page topic guides for students who are not yet able to retain all the key information and remove these as their confidence and knowledge develops.

2. Think beyond the Haber process

Haber and his eponymous process have a tendency to dominate the case studies for the compromise between rate and equilibrium. Overemphasis of this one process can make the concept seem like something to be rote learned rather than understood. This can undermine student approaches to unfamiliar examples that they might encounter in an exam situation. There are other examples you can refer to, such as the contact process. You can even make up your own using fictional reactants and products (eg, A + B → C) together with energy change data. This gets students used to properly examining the information given in questions instead of relying on memory.

3. Work on clear expression

The most common complaint from examiners when students tackle questions about compromises between rates and equilibria is lack of clear expression. When faced with lots of blank lines to write on, students often try to fill the space with sentences, repeating themselves and losing their train of thought. The usual strategies for longer answers can help here, although it is a tough habit to break for many students. Help students to see the benefits of these strategies by providing opportunities for time-limited practice. They will be far more successful under time pressure when they use proper strategies, but they need to see this to believe it!

4. Encourage organised answers

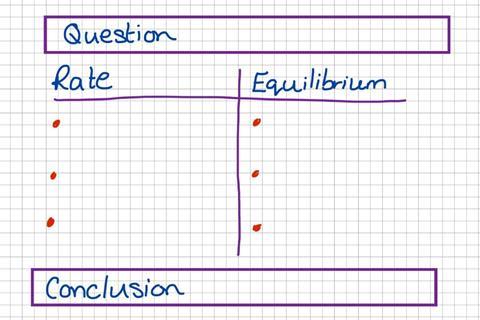

Another common student error is failing to treat both aspects of the question equally. They write extensively (often about rate) and then, seeing they have written a lot, give up before finishing the answer. Consider getting them to make a table of their answer with the headings ‘rate’ and ‘equilibrium’. They can then organise their bullet points below these headings.

Using this table approach in formative assessment exercises helps less confident students to build up to giving a complete answer, as it is easy to see what is missing. They will often begin by making one or two points about rate and you can then encourage them to add a point about equilibrium, and another about rate, and so on.

5. Cut to the conclusion

After the comparison, students need to draw a conclusion. They often forget this after all that work on their explanations. If you’re modelling the table method detailed above, then a box for giving the conclusion is a useful prompt. The conclusion can also be practised on its own: provide students with a model answer, bullet pointing aspects of the comparison, and ask them to write a concluding sentence.

1 Reader's comment