Use these strategies to ensure all 11–16 learners understand salt forming experiments

The chemical reactions that lead to the formation of salts are exciting for students, with lots of nice experiments, colour changes, fizzes and pops. However, beyond this there is a large amount for students to learn and the exam boards use a wide range of question types to check understanding.

Most of the concepts aren’t difficult. Learners study many of the reactions at 11–14 and then revisit them with greater challenge at 14–16. When revisiting the topic, you will often have to adapt learning to a wide range of understanding because some students will have retained the knowledge well, whereas others won’t remember anything at all. Here are four tips to help you meet everyone’s needs in this important topic.

1. Emphasise rules and simplicity

The range of reactions that produce salts can be overwhelming to students. They might feel there is a lot to remember, especially if they study each type of salt forming reaction at different times in their chemistry course. Emphasise to students that they only need to learn the general equations for the reactions and the principles behind the naming of salts so they can then apply these to any reagent combination. Give them plenty of practice and they should begin to see the patterns for themselves and develop some automaticity in applying the key knowledge.

2. Practise choral response

Embed the general pattern for the reactions of acids that make salts with regular repetition. One high impact way to help this information stick is to practise it in choral response. This technique involves all students giving a verbal response when the teacher signals. For example, you might say ‘acid plus alkali gives …’ and students respond on cue with ‘salt plus water’. Choral responses are useful when answers are short, the same each time and when the aim of the activity is to recall facts.

Using this technique takes confidence and both teachers and students need practice. But if this suits your teaching style and personality, it is a great way to help students form strong memories. My year 9 teacher used choral response when I was learning these reactions. The technique stuck so well I still remembered it more than a decade later when I began teacher training.

3. Make practical work purposeful

There are lots of lovely experiments that you can do in this area of chemistry and it can be easy to get carried away exploring them all. However, it is important to reflect on the purpose of each experiment and tune your teaching to specific goals; it is not enough to focus on just carrying out the practical. You might choose to emphasise skills in making careful observations and recording them appropriately or representations of apparatus. Make sure you communicate the practical work’s aims clearly, so students know what success will look like. Consider whether reduced or microscale experiments might be just as effective as standard scale ones, decreasing waste and risk in the process.

There are lots of lovely experiments that you can do in this area of chemistry and it can be easy to get carried away exploring them all. However, it is important to reflect on the purpose of each experiment and tune your teaching to specific goals; it is not enough to focus on just carrying out the practical. You might choose to emphasise skills in making careful observations and recording them appropriately or representations of apparatus. Make sure you communicate the practical work’s aims clearly, so students know what success will look like. Consider whether reduced or microscale experiments might be just as effective as standard scale ones, decreasing waste and risk in the process Find a range of microscale resources on the RSC Education website (rsc.li/419UiBl).

4. Use chemical equations to scaffold descriptions of observations

4. Use chemical equations to scaffold

It is common for examiners to ask students to describe observations of reactions that form salts, typically for two marks. Students tend to describe the most obvious, for example when the reaction of an acid and metal or acid and metal carbonate forms a gas. In practice, get students to use a chemical equation to scaffold their descriptions so they have enough observations to gain all the marks. This can be a word equation or a balanced symbol equation with state symbols for those who are secure in the basics.

Sodium bicarbonate + hydrochloric acid → sodium chloride + water + carbon dioxide

For the reaction producing sodium chloride above there are only two possible observations – you will gradually no longer see white sodium bicarbonate powder and the reaction will produce bubbles – but for others there may be more. For example, a reduction in the size of a piece of metal or a visible colour change. Make sure your students have the correct language for the changes because it’s common to see answers such as ‘CO2 produced’ which isn’t strictly an observation.

Use these tips alongside your favourite activities and see if you can create memories that last 30 years, like my chemistry teacher did.

More salt?

- Watch the Preparing a soluble salt practical video for tips to share with 14–16 year-old learners when making a sample of pure, dry, hydrated copper sulfate crystals from copper oxide.

- Guide learners to recognise hazards, evaluate risks and identify control measures with this student risk assessment worksheet.

- Read this article to explore salt in the diet. Download the accompanying resource to give 11–14s everyday context to fundamental chemistry topics and separation techniques.

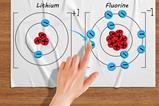

- Demonstrate the reaction between sodium and chlorine to illustrate how the properties of compounds and their constituent elements differ.

- Use the Salt (for cooking) presentation slides, student workbook, teacher and technician notes in a sequence of timetabled lessons, STEM clubs or as part of an activity day.

Kristy Turner

No comments yet