Everything you need to know

-

- Salary range: £25–40k

- Minimum qualifications: PhD or equivalent experience. A PhD in a scientific subject (or experience equivalent to a PhD in such a subject), the most common being chemistry and physics. You will need specialist background knowledge about the chemistry and physics of materials combined with knowledge about history, geography and art.

Undergraduate degree studied at: Università degli Studi di Palermo - Skills required: Attention to detail, analytical skills, data analysis, report-writing skills, communication skills, problem-solving skills.

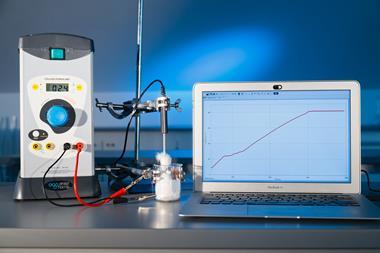

- Training required: Training in how to use specific laboratory equipment.

- Work–life balance: Other activities include training and supervising others, writing grant applications, collaborating with colleagues from other institutions, contributing to strategic museum planning.

- Career progression: There may be the opportunity to progress to more senior roles such as Head of Department.

- Locations: Find related work experience positions using our map of employers

More profiles like Lucia's

What is a museum scientist?

Some types of museum scientists examine objects in detail and find out how and what they are made of, in order to add to our understanding of craftsmanship and art history and to find ways of preserving the objects for future generations to enjoy.

How were you inspired to work in chemistry?

I had always been interested in how things work, and in the properties of different materials – when I was 10 I was already experimenting with melting different types of metals in my kitchen. Then I started studying chemistry in school at the age of 15, and that was the lightning bolt for me, I just fell in love with it. I thought chemistry would give me the chance of a decently-paid job, and a job I would also enjoy doing.

What do you love about your job?

The actual museum objects: the thrill to touch history with my own hands. There’s also the “puzzle aspect” of the job: there is no prescribed way to address a problem, I need to start each time from a blank slate and find a solution, piece by piece, which can be different each time. I enjoy the opportunity to train younger people. And I like the interaction with colleagues and collections from other institutions worldwide.

What is your typical day like?

Every day is different: what I have in my schedule depends on what the museum is planning for the next few months/years, what exhibitions will be opening, what books the curators will be writing, what questions crop up about specific objects and so on. I have to be ready to shuffle tasks and analyses around depending on any new urgent or priority jobs that suddenly come up. Then there is the evaluation of the scientific data, the writing of the relevant report, and the discussion of the results with the museum colleagues who asked me to do the analysis in the first place.

My practical tasks involve the analysis of objects by various scientific techniques, for example:

- investigating the precious metal alloy in a piece of jewellery

- characterising the type of glaze and decoration in a porcelain object

- identifying the pigments on an illuminated medieval manuscript or an oil painting

- characterising the corrosion on a metal object to help the conservator decide what the best treatment is

- analysing the fibres in a textile

- identifying a gemstone on a jewel or the stone material in a sculpture.

Other activities include training and supervising others, writing grant applications, collaborating with colleagues from other institutions, contributing to strategic museum planning. I provide support to other museums who do not have scientists; I write and publish scientific papers, but also blogs and articles for different audiences. I review other scientists’ papers on behalf of scientific journals, and evaluate research grant applications for external funding bodies.

What tips or advice would you have for someone looking to get into science at a cultural institution?

My advice is to study your chemistry and physics religiously, but cultivate other aspects of your background knowledge too, especially history and art history. Learn as much as you can about as many topics as possible, be curious, inquisitive and try and learn from as many sources and people as you can get access to.

How did your qualification help you get your job?

I did chemistry at university but came from a classical background – my parents teach Latin, Greek and literature. The structures I learned in school, such as grammar and logic, dovetailed nicely with science and gave me a nice broad skill set.

I left school with the equivalent of an international baccalaureate. My 5-year undergraduate degree in chemistry covered inorganic, organic and physical chemistry. I acquired additional cultural heritage expertise during the Erasmus programme when I worked on the spectroscopic analysis of pigments on medieval manuscripts. That led me to choose a PhD in chemistry in a related topic. With this type of postgraduate experience, working in a museum was the ideal option for me and I started applying for jobs in museums and galleries. I was offered a job in banking, and I could have made a fortune, but my passions lay elsewhere. I had no idea I could combine them until the V&A job came up.

Want to find out more?

- Read Lucia Burgio’s blog and find out more about conservation at the Victoria & Albert Museum

- Speak to the scientists working in museums and cultural heritage institutions

- Explore the heritage science technical briefs curated by the Analytical Methods Committee for the Royal Society of Chemistry who describe how different analytical techniques can help in cultural heritage.

- Look for opportunities for summer internships in museums’ scientific laboratories to experience first-hand what the job entails. The V&A offers student placements.

- For more routes into heritage and conservation science and the types of roles available see the National Career Service.

First published 2021