Need some fake snow for your Christmas party? Simply look inside an astronaut’s suit

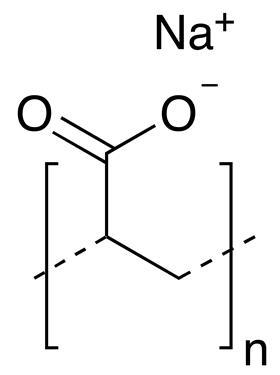

There’s an unlikely connection between disposable nappies and fake snow: the chemical sodium poly(acrylate). This chemical is a polymer made up of long chains of repeated acrylic acid subunits joined together. In its dry powder form, positively charged sodium ions are tightly bound within a cage of poly(acrylate) chains, kept close by negatively charged carboxyl groups dangling from the polymer backbone. But add water, and the interactions change. Replaced by positively charged hydrogen ions in the water, the sodium ions are free to go on the move and the tightly organised polymer chains begin to unravel. They don’t completely separate and dissolve, however, instead forming a stiff, swollen gel.

This clever chemistry means that sodium poly(acrylate) can absorb and lock away huge amounts of water. It can hold up to 300 times its mass in the case of tap water (which contains other metal ions that compete with the hydrogen ions) or up to 800 times the mass of ion-free distilled water.

Super-absorbent polymers, such as sodium poly(acrylate), were first developed in the late 1960s by the US Department of Agriculture. They were searching for ways to hold moisture in the soil more effectively. Early attempts were based on starch – a naturally-occurring polymer made from glucose molecules strung into long chains, which swells up when water is added. They added other chemicals to the mix, such as acrylonitrile, acrylic acid, acrylamide and poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA), and finally moved away from the starchy backbone altogether.

Eventually, researchers created polymers that could absorb hundreds of times their own weight in water, and keep it there. This was a big improvement on adsorbent materials available at the time, including tissue paper, sponge, cotton wool or fluffy wood pulp, which can only manage to absorb around 20 times their weight in water. And the water can easily escape back out again.

By the 1970s manufacturers were quick to spot uses for these super-sucking polymers. First they were used in sanitary towels and adult incontinence pads. Disposable nappies came in the early 80s, followed by absorbent pads and baffles for industrial spills, and even absorbent suits for busy NASA astronauts unable to pop to the loo.

This kind of fake snow actually looks a lot more like snow than the real thing

Today, sodium poly(acrylate) is used as a thickener in hair gels and other beauty products, as well as in those jelly-filled cold packs that you pop in the freezer. It’s non-toxic, so very safe, although it can cause irritation and burns if it gets into the eyes. It’s also mixed into some types of coatings for electrical wires, to wick away water and keep them dry. And, of course, based on the original goal of those 1960s scientists, sodium poly(acrylate) and similar super-absorbant polymers have found a host of agricultural uses, such as keeping soil or cut flowers hydrated.

But what about fake snow? When mixed with water, the properties of the resulting gel depend on the amount of crosslinking between the polymer chains. Sodium polyacrylate and similar compounds have relatively few cross-links, so the gel can swell a lot and suck up lots of water. But a different version, known as PolySnow™ has a lot more cross-links, and swells up to make tighter, dryer flakes that look a lot more like snow than the splodgy, wet gel found inside a nappy. When seen on screen in the movies, this kind of fake snow actually looks a lot more like snow than the real thing. And it doesn’t melt – a property that is ‘snow joke’ for film directors trying to shoot winter scenes in warmer temperatures!

No comments yet