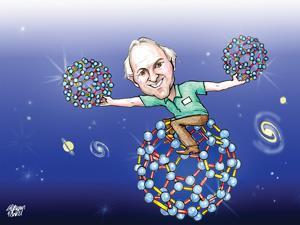

Nina Notman pays her respects to Harry Kroto, a co-discover of the buckyball

Harry Kroto is undisputedly best known for his role in the discovery of C60: buckminsterfullerene. But this was only a tiny part of his life’s work, and maybe surprisingly, not the piece of research he was most proud of.

In an interview with Chemistry World in 2015, Harry explained that figuring out how to make molecules containing a carbon–phosphorus double bond gave him the most intellectual satisfaction. ‘People thought you couldn’t do it,’ he explained.

The 1985 discovery of C60, however, was one of the trigger points for the start of a far larger research area: nanotechnology. C60 was discovered almost by accident. Harry spent much of his career synthesising straight chain carbon molecules he believed might exist in outer space, and then using microwave spectroscopy to study them and see if their signals did indeed match those being recorded from space.

As part of this work, he travelled to Rice University in the US to use an instrument designed by Richard Smalley, a co-recipient of the 1996 Nobel prize. They zapped graphite with a laser and measured the mass of the fragments released. The team were looking for relatively low mass molecules, but it turned out the C60+ ion was the dominant fragment.

They worked out that molecule must be shaped like a football, and Harry coined it buckminsterfullerene after the architect Buckminster Fuller who designed similarly-structured geodesic domes.

Publication of this work was followed by five years of balking from disbelieving members of the scientific community. But eventually, larger quantities of C60 were synthesised and proved to have a perfect spherical shape.

This was the first new form of carbon to be discovered for millennia, and it spawned the synthesis of many others. Of those made by Harry, he often said C28 was his favourite.

For Harry, there was always an unfinished chapter in the tale. No-one had actually found evidence that C60 exists in space. But two years ago a research team finally proved C60+ ions are all over the galaxy: a finding that thrilled Harry.

After winning a Nobel prize, Harry dedicated much of his time to education and lending his voice to various campaigns he supported. Funding for fundamental science was a topic he frequently spoke passionately about.

But it is his education work for which many of us have our fondest memories of Harry. I myself met him with a buckyball made of modelling balloons upon his head. He was enthusing a group of university students about the merits of a scientific career during a boat trip on Lake Constance in southern Germany at the time, but I suspect many of you could tell similar tales of a charismatic Harry finding ways to simultaneously thrill and educate young people all over the world.

And with that I say farewell to a stellar scientific educator: you will be missed.

Sir Harry Kroto, 1939–2016

No comments yet