For the past 200 years violin makers around the world have sought to produce violins that would rival those of Stradivari and Guarneri made during 1700-50.

For the past 200 years violin makers around the world have sought to produce violins that would rival those of Stradivari and Guarneri made during 1700-50. Could, for example, the chemical treatment of the wood, intended to kill woodworm and fungi, have imparted the characteristic brilliance and low noise level to the tone of the musical instruments made in Cremona, Italy? This chemical paradigm lends itself to experimental verification.

The chemical paradigm1,2 could only be proven by material analysis of samples taken from the famous instruments of Antonio Stradivari and his chief rival, Joseph Guarneri (known also as del Gesu). Such analyses would need to focus on the methods of wood preparation and finishing technologies, and how these differed from those of later periods. Unfortunately, the owners and restorers of these famous instruments have remained cool to the idea of handing over their treasures to a chemist with scalpel and hypodermic syringe in hand. During the past 30 years, however, I have managed to acquire a handful of authentic specimens. While these do not allow one to generalise about the diverse chemical methods that could have been employed in Cremona during the two centuries of its golden age, the limited findings of my research group are exciting since they fit into the historical expectations and have stimulated reconstruction experiments.

To soak or not to soak?

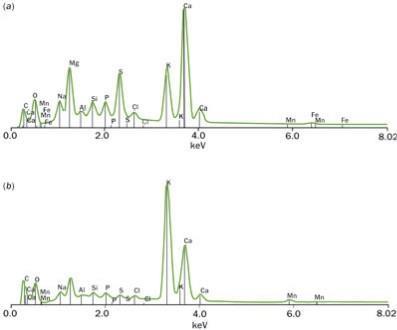

The most convenient method of modern instrumental analysis for small specimens is EDX (energy dispersive x-ray) spectroscopy, which involves bombarding a sample with an electron beam; the energy of the resulting x-rays is characteristic of the element from which they are emitted. We first applied this method in 1980 to wood chips from a cello by Andrea Guarneri (Joseph's grandfather) and found that Si, K and Cl were the dominant elements, among several minor components. This composition could be compatible with a past history of soaking the original wood in a suspension of wood ash in water. However, similar results would have been obtained, for example, by using grape juice and diatomaceous earth, or wine mud, which contains the silica filtration medium, various polysaccharides and potassium hydrogen tartarte crystals. Moreover, single EDX scans are only semi-quantitative, for more accurate analysis the wood chips need to be burnt to an ash, which can then be compressed and repeatedly analysed. We used this method on a maple sample from a Stradivarius cello, the results of which are shown in Fig 1. In contrast to the Guarneri sample, the mineral composition of the Stradivari maple suggests that at least one soaking solution used could have been a local mineral water since we found high concentrations of Ca and Mg. (Mineral waters in Northern Italy are rich in calcium and magnesium salts.)

However, our results do not rule out the possibility that the wood used was natural and only the finished instrument was wetted with an aqueous salt solution many times both inside and out. It is very unlikely that brushing an aqueous solution onto the interior surface of the instrument would penetrate deep enough to change appreciably the mineral composition of the deeper layers of wood. Moreover, violin makers tended to limit themselves to one aqueous brushing lest they jeopardise the integrity of the glue joints. Nevertheless, we decided to examine the organic constituents of the wood, which is made up of cellulose (repeating glucose units connected by oxygen atoms), hemicellulose, and lignin (a phenylpropane polymer, and the non-carbohydrate component of wood).

Figure 1 - EDX spectra of: ( a) maple wood from a Stradivari cello; and ( b) recent maple wood. (Both spectra represent the average of 10 scans.)

IR analysis of wood slivers

For the non-destructive analysis of the old wood slivers we used infrared spectroscopy. I was fortunate to have ir specialist, Dr Noel Owen, to do this for us. He and his team at Brigham Young University compared the infrared spectra from the maple back of the Stradivari cello, the del Gesu violin, an old English viola made by Henry Jay and a French violin by Gand with a new maple sample. Their results pointed to the two Cremona samples having slightly reduced hemicellulose content compared with samples from the other instruments.

A more sensitive method of assessing changes in hemicellulose would be the direct measurement of one of its minor carbohydrate components. Dr Mark Davis of the Forestry Products Laboratory of Wisconsin analysed the arabinan content of the Stradivari maple and natural maple. (A component of hemicellulose, arabinan is the polymer of the sugar arabinase (C5H10O5) with a repeating unit of C5H8O4.) He found that the Stradivari maple contained 0.37 per cent arabinan, while the natural maple had 0.83 per cent, ie the Stadivari maple had significantly less hemicellulose than the natural wood. Unfortunately, we did not have enough quantities of the del Gesu maple for this destructive analysis.

We subjected our remaining samples to C-13 solid state NMR spectroscopy to determine any changes in the organic matrix. Dr Joseph DiVerdi of the NMR Laboratory of Colorado State University, ran the spectra for us. DiVerdi's results revealed that the maple wood from the del Gesu had less acetyl groups than the natural wood, suggesting that the del Gesu had been treated with a basic solution, such as potassium carbonate or borax. This finding fits well with the EDX spectrum of another del Gesu, which indicated the presence of wood ash components that contain the strong base potassium silicate. Boiling alone in water at neutral pH for 24 hours would not cause such a noticeable decrease in the acetyl component. Interestingly, however, the maple of the Stradivari cello showed no evidence of a past alkaline treatment. Unfortunately, we did not get the chance to examine a sample from a Stradivari violin, so it is impossible to tell if the methods of the two leading masters were fundamentally different, or the instrument size warranted different aqueous treatments.

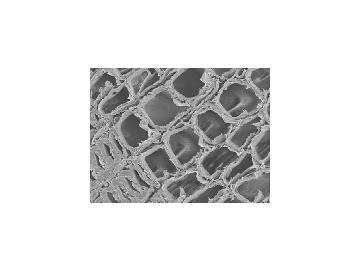

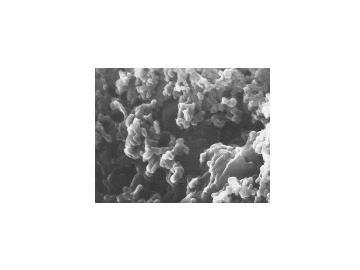

As exciting as these findings are, they don't solve the mystery. According to a few people who tried it, aqueous treatment has only a deleterious effect on the stiffness of wood, and such treatment does not seem logical.3 Apparently, there is much more to successful violin making than selecting the wood by its maximum Young's modulus (stiffness).4 There are other and probably more relevant consequences of boiling the wood, or soaking it with alkali solutions. For example, we have determined that according to the conditions, the water content of the dried wood can be reduced from about 12 per cent to 6-8 per cent at 50 per cent relative humidity, conditions typical of Cremona's humid climate. Such treatment would also loosen the cell to cell adhesion. This can be seen on cutting the wood across the grain with a razor blade as shown in the scanning electron micrographs (SEMs) of natural wood and boiled or wood ash treated wood (see Fig 2). The treated wood has a significantly increased permeability, especially to organic solvents, and this may be important in the final stage of violin making, the finishing process.

Figure 2 - SEM of: (top) natural wood; (bottom) treated wood

The Cremona finish

A protective coating is applied to the surface of the carved and assembled instrument in the process known as finishing or varnishing. These terms are often used interchangeably, but there is a difference. The former also includes adding wood filler, ie the first matter (solid and liquid) that enters the pores of the wood. The varnish more often refers to the transparent films of diverse resinous materials which are layered on top of the filler.

The greatest breakthrough in our knowledge of the finishing technology used some 200 years ago came from the craftsman F. S. Sacconi in 1972 who said that Stradivari's filler could have been a potassium silicate solution.5 (My guess would be that a local chemist - the unsung hero who has remained unacknowledged - provided the analytical data to him.)

We were not particularly surprised therefore that K and Si were the major elements in the Guarneri wood/filler fragment that we analysed by EDX in 1980. What was rather unexpected was that none of the samples we obtained in 1984 and 1985 - one Stradivarius, one F. Ruggeri, one N. Amati and one from the Venetian D. Busan - contained significant quantities of K-silicate. We looked at more than 200 particles in the electron microscope and identified 24 mineral species. At about the same time, Barlow suggested tentatively, on the basis of a single EDX run,6 that Stradivari's filler could have been a kind of volcanic ash. Although the presence of some ash cannot be ruled out, the transparency of the finish rather suggests that finely crushed mineral crystals, like quartz, calcite, feldspar and gypsum, were the main components of the filler powder in most instruments.

Two remarkable attributes of the Cremona finishes impressed me when I had the chance to poke them with a hypodermic syringe. (In addition to the violin, viola and cello samples I have already mentioned, this year I was given the chance to examine a famous double bass made by an unidentified maker in Cremona. This bass was once owned by Serge Kroussevitzky and currently by the American virtuoso, Gary Carr.)

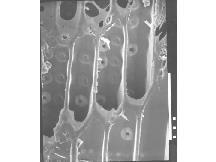

First, all coatings on all the instruments were extremely brittle and fractured like thin layers of ceramics. In contrast, modern varnishes remain cohesive like plastics. The double bass varnish was the most fragile. This varnish lacked the soft outer layer found on the Stradivari and Ruggeri, which were almost certainly applied by restorers. This soft overcoat gave enough cohesion to the square millimetre sample area to allow me to uplift a fragment from the deepest filler layer all the way to the top. The cross section of an exceptionally beautiful Stradivari varnish, which was photographed for us in a light microscope under crossed polars by Dr Robert Muggli of McCrone Associates is shown in Fig 3. Unlike the popular French varnishes, which are quite homogeneous, the varnishes of Stradivari and Ruggeri, who happened to be neighbours, had a clear separation of several colours and different particulate matter.

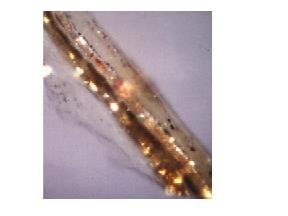

What also impressed me was the fineness of the particles within the varnishes. This is especially true for the Stradivari varnish which is made up of microcomposite (see Fig 4) or even a nanocomposite matter. Producing the refined micron-size powder by the primitive grinding and separatory techniques of the period must have been difficult. To the extent that the chemicals procured from the drugstore had a major influence on the acoustical outcome of the finished violins, the local chemist could be viewed as the unsung hero standing in the shadow of the celebrated masters. Would it not be time that the chemist received his due credit?

I can only theorise about the acoustical consequences of the old wood treatment and finishing technology as they differed from the current ones. The vibrations of the violin,7 which encompass a wide range, from the low frequencies to the ultrasound, can introduce fractures both in the wood structures and in the finish, causing visible crack lines and invisible micro-cracks in the interior. This may enable the anti-nodal points of the plates to move outward with greater amplitudes as the cracks open up. The result would be a musical sound which has both strong fundamental tones and commensurate overtones. The much appreciated open clarity of the Stradivari and del Gesu violins may also be attributed to their low noise level. The microstructure of the wood and varnish, as they were informed by the chemical composition, may have generated the underlying noise filters.

Figure 3 - The legendary Stradivari varnish

Figure 4 - SEM of Stradivari varnish at 10000x magnification

Conclusions

What we have seen and deduced from a limited sampling of famous musical instruments should only increase our admiration for the old craftsmen and their chemical collaborator. Yet it is possible that neither the violin maker nor the chemist were aware of the acoustical consequences of the chemical manipulations which were intended to protect against woodworm and fungi. These were not among the trade secrets they would have passed on to the next generation, and the change of preservation technology could have led to a decline of the art even in the same city of Cremona.

In writing this article I would like to think that some of you would continue with the unfinished business of acquiring and analysing more samples from the famous antique instruments to broaden our knowledge. Perhaps some of you would be more diplomatic and successful than I was on dealing with collectors and restorers, who control access to these treasures worth millions of dollars.

Joseph Nagyvary is professor emeritus of biochemistry at Texas A&M University College Station, Texas 77843 and owner of Nagyvary Violins.

Box 1 - Joesph Nagyvary's lifetime investigation

In 1958 Joseph Nagyvary's neighbour and violin maker Amos Segesser expressed a wistful admiration for chemistry, which he felt would hold the key to finding the secrets of the old master luthiers of Cremona. Since then, Nagyvary has been doing research in this area. During his many trips to Italy in the 1960s, he noticed that wooden artefacts were riddled with woodworm, except those from Cremona. He reasoned that the Cremona wood must have been preserved, and was soon investigating the connection between the chemicals used to preserve wood with the great acoustic effects. Among his many investigations, Nagyvary has considered borax, an insecticide and crosslinker of polymers, which would make the wood tighter and harder, and sound more brilliant; various sugars from the plethora of fruit trees in Cremona, which could have been used against mould; fine quartz powder, which could have been added to saturate the wood - woodworm won't chew crystals - and many other fillers. He comments:

Personally, having entered my seventies, I take great comfort from the fact that Stradivari's best period began in his seventies and continued throughout his eighties into his nineties.. Inspired by the past and recent results of the chemical analysis, we have made so far over 150 violins by many variations of the aqueous processing and composite finishes. Their evaluation began with positive comments by Lord Menuhin - who owned a 'Nagyvarius' - and Isaac Strern and is being continued by several young virtuosos.

Related Links

Nagyvary violins For more on the background of our processes and products go to www.nagyvaryviolins.com

References

- J. Nagyvary, Chem. & Eng. News, 23 May, 1988.

- J. Nagyvary, The Chemical Intelligencer, 1996, 2 (1), 24.

- D. W. Haines, The Catgut. Acoust. Soc. Newslet., 1979, 31, 23.

- V. Bucur, Acoustics of wood. New York, London: CRC, 1995.

- S. F. Sacconi, The 'secrets' of Stradivari. Cremona, Italy: Libreria del Convegno, 1972.

- C. Y. Barlow et al, Nature (London), 1988, 332, 313.

- L. Cremer, The physics of the violin. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 1983.

No comments yet