Positive role models are key to attracting a more diverse section of society to the chemical sciences. Nina Notman reports

The make-up of people studying and working in chemistry in the UK does not reflect that of the wider population, explains Lesley Yellowlees, the immediate past president of the Royal Society of Chemistry. ‘We need to ask ourselves why, and what is it that we are doing that is not encouraging people from certain backgrounds to take up a career in science.’ Promoting inclusion and diversity has been the cornerstone of my presidency, she says.

‘Diversity is important because chemistry is diverse,’ explains David Smith, a professor of supramolecular and nanoscale chemistry at the University of York. ‘There are diverse problems to solve in diverse communities around the world and there’s a huge diversity of chemical approaches we can take to solve them. If we limit who can and can’t be chemists, then we’re not going to find answers to that diverse range of problems.’

The RSC uses the term diversity to encompass differences in culture, background and experiences. Examples of these differences include race, ethnicity, gender, disability, sexual orientation, age, socioeconomic classes, religious affiliations, and career status and career path.

Support, says Lesley, is the key to achieving a greater diversity of people pursuing careers in chemistry. Teachers and parents need to be supported to ensure all pupils are introduced to the excitement and pleasure of the subject at a young age and students must then be encouraged to retain their interest in the subject throughout school, she says.

More also needs to be done to retain people within the subject after undergraduate degrees as they move through their careers. This is a major dropping off point for some sections of society, especially women. Historically, chemistry has been a male dominated discipline and much has been done to encourage more women to study the subject at university. ‘The latest figures for Edinburgh show that more than 50% now coming in at undergraduate level in chemistry are female,’ says Lesley. ‘But if you look at the professorial level, it is 7–8%.’

To encourage and retain a diverse community within chemistry, ‘we have to look at things like unconscious bias, mentoring for our young people, flexibility of working conditions and how best to support everybody throughout the whole of the lifespan of their work’, she says.

The promotion of positive role models is another well-established approach to encouraging diversity within a community, and Lesley herself is an excellent role model for female chemists. She is a professor of inorganic electrochemistry as well as vice principal and head of the college of science and engineering at the University of Edinburgh, and was the first female RSC president.

Lesley, during her presidency, initiated a project called 175 Faces of Chemistry. The RSC is publishing the profiles of 175 diverse chemists on a dedicated website in the run up to the RSC’s 175th anniversary in 2016. ‘I hope that these chemists can be seen as role models,’ says Lesley, ‘and I’m hoping that with 175 different faces, everyone will find someone they can relate to.’

A hidden diversity issue

‘Role models are one of the most powerful things, particularly for people coming into a career, seeing that people like them can succeed can act as a real inspiration,’ agrees David, who is one of the 175 Faces of Chemistry.

Sexuality is a hidden diversity issue, he says. ‘There aren’t, if you look around, many “out” gay scientists – especially in chemistry,’ he says. David himself is openly gay. ‘I think it’s important that students see that a wide range of people get involved in chemistry and that your background and personal life are not barriers to achievement.’

David recently surveyed ‘out’ LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender) chemistry undergraduates at the University of York. ‘I found that they find the department a remarkably inclusive and safe space, and that they really appreciate the presence of “out” staff members and other students, which allows them to feel that not only will they not be discriminated against, but that they can succeed at the highest levels in their own careers.’

The University of York chemistry department has an excellent track record for promoting diversity and inclusion. It was one of the first departments to receive an Athena SWAN gold award for its commitment to advancing woman’s careers in STEMM (science, technology, engineering, medicine and mathematics) academia. ‘That changed the ethos in the department to a whole range of different issues,’ says David, ‘and the department started to think about inclusivity in very general terms.’

Overcoming adversity

Someone with personal experience of the University of York’s inclusive environment is Cheryl Alexander, another of the 175 Faces of Chemistry, who graduated from the university with a MChem in 2004, a MRes in clean chemical technology in 2006, a PGCE in 2007 and is currently working towards a MA in education. Cheryl has mobility problems and uses a wheelchair, but during her undergraduate degree she was still able to walk using crutches and leg braces. ‘The university helped any way they could, particularly my supervisor. The technicians were also very good at helping me find ways to do things, like giving me a bottle basket to carry things around the lab,’ says Cheryl. With the help of her assistance dog, Cheryl now teaches chemistry at York High School.

‘I have been fortunate enough to meet and to teach young people with disabilities,’ says Cheryl. She says that some disabled children have benefited from seeing her and other disabled adults just getting on and living their lives. ‘They can see that there need not be limits on the kind of adult they can become. It is easy, even without acknowledging it, to believe that a career, a programme of study or a particular lifestyle is closed to you, simply having never seen someone like you do it,’ she explains.

Cheryl can also see the advantages of able-bodied children seeing disabled adults living happy and fulfilling lives. ‘I have met lots of people who react with surprise and admiration when they find out I work, and I don’t think any of the kids I have taught will think like that,’ she says. ‘I think the more people who are different to them that they see just being ordinary people, the better.’

‘The biggest challenge I have faced [however] was not my disability, but my background,’ says Cheryl. ‘I did not come from an academic background, nor a prosperous one.’ At 14, however, she was fostered. ‘My foster parents were very educated, kind and tolerant people, who seemed to be interested in everything. This was very inspirational to me.’ She also credits a number of her own chemistry teachers who inspired her to both attend university and study chemistry.

David also says that inspirational school chemistry teachers were the key to his success. ‘I went to a big state school in Stockport,’ he says. ‘There weren’t many people from my school who went to the University of Oxford – that was a pretty unusual path to tread.’ However, his two chemistry teachers there both excited him about the possibilities chemistry offered and convinced him to study the subject at university.

Not enough men

When discussing gender in the context of diversity and chemistry, we tend to think about the need to encourage more women into the chemical community. But in the teaching profession it is males that are in the minority. In 2013, over 73% of all teachers in UK state schools were female.

Someone with first-hand experience of this is another of the 175 Faces of Chemistry, Edwyn Anderton. After a PhD in chemistry, Edwyn trained as a primary school teacher and spent 10 years in the classroom. He is now a senior lecturer in primary and early years education at Sheffield Hallam University.

‘My first teaching job was in a catchment area containing high numbers of single parents – I was the only male member of staff and often the children appreciated a male figure in their lives,’ says Edwyn. ‘There are certainly increasing numbers of men entering primary teaching so although it is still unbalanced it is improving.’

He believes the key to encouraging diversity in the chemistry community is addressing people’s attitudes and preconceptions. ‘If [students] are encouraged to study science and shown that they can be good at the subject, then they will be prepared to advance further,’ he says. ‘From my experience, primary school teachers are very good at this inclusive practice but sometimes face negative attitudes from the children’s home life (which includes media they are exposed to outside school).’

Moving country

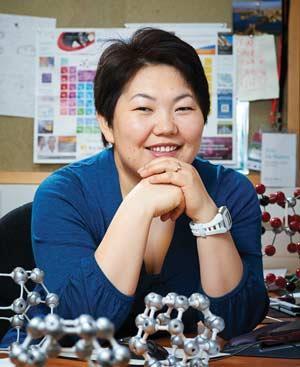

Asel Sartbaeva, another of the 175 Faces of Chemistry and a research fellow working on flexible framework structures at the University of Bath, also credits strong role models for her success.

Asel was born in Kyrgyzstan, a small country in Central Asia that became independent following the break-up of the former Soviet Union. ‘When I went to study physical sciences at the Kyrgyz-Russian University in Bishkek, women were a very small minority and I was the only Kyrgyz woman on my course,’ she explains.

‘My mother was always my role model; she successfully built her career and independence despite many obstacles. She encouraged me to pursue my dreams and to believe I could succeed.’ Asel’s school chemistry and maths teachers were also strong female role models. ‘I had a great chemistry teacher in secondary school; she was very strong and later on she became the head of the school.’ In the 1980s in the former Soviet Union, heads of school were always old men, Asel explains.

After her first degree, Asel applied to the University of Cambridge for postgraduate studies. And having tackled questions such as whether Kyrgyzstan was a real place, she was offered a place to study for an MPhil and then a PhD. ‘As far as I know, I was the first Kyrgyz to receive a PhD at Cambridge; I hope there will more after me,’ says Asel.

At times in her career, though, Asel has experienced discrimination due to both her sex and ethnicity. ‘I think the fact that I am where I am now shows that we have gone far in addressing the diversity issues, but there is still much to be done,’ she says. ‘I hope by the time my daughter grows up, society as a whole will be more accepting of many personal differences and backgrounds.’

The RSC is inviting the community to nominate people to be profiled as part of the 175 Faces of Chemistry project. Nominees can be living scientists or historical figures, come from all spheres and sectors of chemistry, and from inside or outside the UK.

Nina Notman is a science writer based in Salisbury, UK

No comments yet