How to recognise and remove microbarriers using adaptive teaching to improve SEN students’ access and progress in learning

The facts around special educational needs (SEN) in our education system make for grim reading. The proportion of students with diagnosed needs is rising, the attainment gap between SEN students and their peers is widening (p2 of Guidance report pdf) and funding cuts are rife. It is no wonder then, that you don’t see public-facing school performance data broken down by SEN. You can compare schools by disadvantage, gender, prior attainment and English as an additional language, but not SEN. Presumably because it’s embarrassingly poor almost everywhere.

The facts around special educational needs (SEN) in our education system make for grim reading. The proportion of students with diagnosed needs is rising (bit.ly/4eNxN9R), the attainment gap between SEN students and their peers is widening and funding cuts are rife. It is no wonder then, that you don’t see public-facing school performance data broken down by SEN. You can compare schools by disadvantage, gender, prior attainment and English as an additional language, but not SEN. Presumably because it’s embarrassingly poor almost everywhere.

Hopefully, we are at the low point in SEN funding and the recent change of government will bring about an increase in resources and a higher priority for SEN provision. In the meantime, all classroom teachers have a responsibility for meeting SEN students’ needs (teaching standard 5 in England) whether additional resources are available or not. This can seem a daunting task, especially if you were trained as I was to differentiate resources for SEN students. Thankfully this type of thinking is going out of fashion and adaptive teaching is de rigueur, which is easier for the teacher and more effective as it maintains a high aspiration for all learners.

When we meet our SEN students’ needs in optimum conditions of time, support, motivation and accessibility, there is very little that they can’t do

There is no reason adaptive teaching shouldn’t work for the majority of SEN students. Most physically disabled, dyslexic and autistic students and those with social and behavioural difficulties and ADHD are not intellectually limited. Most SEN students aren’t limited by how much they can learn, they are limited by how easily they can access learning in the classroom largely designed with non-SEN students in mind. SEN students often find tasks more difficult to complete due to microbarriers.

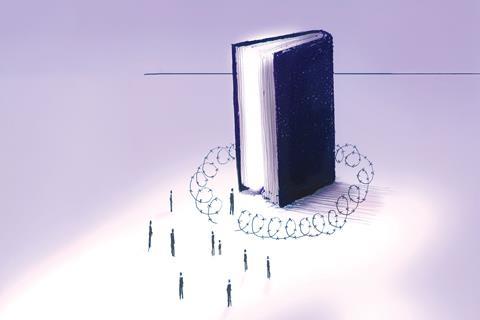

Recognising and removing microbarriers

Microbarriers are the things which stand in opposition to progress but are not insurmountable. We all encounter microbarriers every single day; the photocopier that needs unjamming, the password that needs updating, the lack of phone or wifi signal when you want it. No single microbarrier will stop you from making progress, but they can slow down your progress and make you more tired and irritable. Enough of them in a single day and you eventually lose motivation and give up. There’s a reason student behaviour and engagement are worse at the end of the day.

We are familiar with an adaptive physical environment that seeks to minimise microbarriers for physically disabled people. For example, dropped kerbs and automatic doors are adaptations for wheelchair users. Some wheelchair users may not need these adaptations, but their progress is easier with them. Happily, the removal of these microbarriers also makes other’s lives easier too; parents with pushchairs and those with heavy suitcases also benefit.

Adaptive teaching does the same but for cognitive, rather than physical, microbarriers. When we meet our SEN students’ needs in optimum conditions of time, support, motivation and accessibility, there is very little that they can’t do. There’s no magic bullet here and I don’t want to tell you how to adapt your teaching – you should ask your SEN students (or look at their learning profiles) and adapt accordingly. However here are suggestions based on four common areas of need.

1. Reading microbarriers

Larger text and fonts without serifs are usually easier to read. Pastel rather than white backgrounds produce less visual strain. Remove as many microbarriers to reading as you can. But also ask if reading an extended text is necessary. Could you present the text both audibly and visually simultaneously so those who find reading difficult can listen?

2. Writing microbarriers

Is the writing you’re asking students to do necessary for learning? Eliminate pointless copying from the board. Print information for some or all students to stick in their exercise books. Do all students need exercise books or could they work on mini whiteboards instead? The temporary nature of whiteboards enables students who find writing difficult to relax and emphasises the importance of retaining knowledge in their heads rather than in a book.

3. Attention microbarriers

For students who find concentration hard, ask yourself if they sit in the optimum position in the classroom for focus. Is other students’ behaviour distracting? Are presentations cluttered or posters around the room acting as a distraction? Is the teacher directing students’ attention to the correct place during an explanation? Do worksheets have answer spaces or do students have to split their attention between a worksheet and a book?

For students who find concentration hard, ask yourself if they sit in the optimum position in the classroom for focus. Is other students’ behaviour distracting? Are presentations cluttered or posters around the room acting as a distraction? Is the teacher directing students’ attention to the correct place during an explanation, such as dual coding (rsc.li/3Nof60f). Do worksheets have answer spaces or do students have to split their attention between a worksheet and a book?

4. Motivation microbarriers

Motivation does not lead to success, rather success leads to motivation. All students require success in every lesson. The first question in a starter or on a worksheet must be easy enough to give all learners success. Like a dropped kerb the difficulty can ramp up, but if the step at the start isn’t smooth then it may hinder progress.

Bill Wilkinson is an experienced scientist, teacher and author

No comments yet