Starting university marks a new chapter in a student's life, with a brand new set of opportunities and challenges. But the different teaching style in higher education can prove to be an unexpected shock to the system. Catherine Smith explores what educators on either side can do to ease the transition

Part of what marks university out as a new stage in a student's education is how very different it is from all that they have experienced before. Often they'll be away from home, with new people, studying to a new level - but they will also be expected to learn in a new way. This may be more difficult for some than others, but there are many small steps teachers and lecturers can take to reduce the number of rabbits staring into the headlights on that first day of university.

Objective thinking

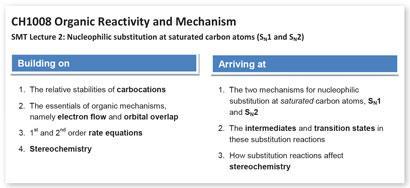

At both school and university, lecturers and teachers are clear about the learning objectives for the lecture or lesson ahead. How, and indeed whether, this information is shared with their learners is the first key difference between the two settings.

Establishing clear objectives or outcomes for a lesson is regarded as good practice at school level.1 They describe simply and exactly what the students should be able to do by the end of the lesson and are displayed throughout; they are differentiated to meet individual students' needs and allow everyone to know what they need to have achieved to have progressed well. Teachers are encouraged to refer to the objectives throughout the lesson and effectively tick them off as learning is achieved.

In higher education (HE), actively using learning objectives is less of a formal requirement and depends on the individual lecturer. A statement of aims, objectives or outcomes can usually be found in the documentation accompanying any given unit of teaching (but whether a student spends time reading said documentation is another matter). Ideally, the learning objectives for a lecture are shared - either on a written hand-out, in the presentation or verbally. This helps students see where the learning is going and position it within the lecture series (fig 1).

Recent research by Boniface et al2 found that using learning objectives in HE helped to scaffold the learning process and support students in their self-study. One student, for example, commented that they found knowing the learning objectives beneficial because they showed 'how one piece of knowledge, once learnt, would assist later on in the course' and that she 'linked certain outcomes to parts of the textbook for easier learning.'

Independent thought

Whether or not learning objectives should be written and shared for all lectures is still a question for debate. At school level, it is ultimately exam boards that dictate what is to be learnt and it is up to the teacher to break it down into manageable chunks for the students. At university level, students must manage their own learning and be able to read around the subject as well as define the key learning points.

This is an element of the transition to university that students often find most difficult. 'But what do we need to know for the exam?' is a common cry among first year undergraduates. Perhaps a phased approach, providing new undergraduates with detailed learning objectives that become less explicit as independent study skills develop would help. At school level, teaching to a wider curriculum and encouraging students to move beyond the course textbook would take them out of the exam board mind-set and begin to help them develop as independent learners.

Starter for 10

Having established 'what' will be learnt during the class, the next question is 'how?'.

At school level, students can arrive in class from any subject and might not have had a chemistry lesson for several days. While the teacher may have instant recall of the last lesson, the chances are that the students will not - starting the class with 'what did we learn last lesson?' can be quite an eye-opener. A starter activity is therefore often used to encourage the students to recap the previous lesson, especially if today's lesson builds upon it.

University lectures could benefit from a similar strategy. Often students arrive in dribs and drabs as lectures in other rooms finish. Having a simple activity displayed on the screen or available on a hand-out as the students arrive requires minimal preparation, reinforces learning from the last lecture, and has the added benefit of allowing the lecturer time to set up and deal with any administrative tasks. Although many lecturers start with a recap of the previous lecture, it is often a very passive process that fails to engage their students.

Pre-lecture activities are becoming more popular in HE,3 but differ to school starter activities by providing learners with material in advance and therefore reducing the amount of new information to be presented and digested during the lecture.

Beyond the lecture hall

Perhaps the most noticeable difference between school and university is when students are expected to actively learn. At school, all learning is to be achieved in the lesson (though it may be supported by homework tasks). At university, the lecture is just the start. Workshops, tutorials and independent study are an equal part of the learning process. Making this explicit to students from the beginning clarifies what is expected of them and will help reduce any anxiety over this new learning approach. A few words at the start of each workshop, tutorial or lecture connecting the content covered in each would benefit the students in their first few weeks of university and help them to appreciate the connection.

Variety of learning experiences

Teaching and learning in school is often influenced by Ofsted's definition of 'outstanding'.4 With an emphasis on checking pupils' understanding throughout lessons and anticipating areas of potential difficulty, learning in the classroom occurs in short chunks followed by activities in which the students demonstrate that the learning has taken place.

In a 2011 report on good practice in science in sixth form/further education colleges, Ofsted commented that the most effective lessons 'consisted of a well-organised variety of relevant and closely linked activities' and that 'best progress was made where students could work together in small groups on discrete activities that led to thought-provoking conclusions.5

In the best lessons, the teacher facilitates learning by setting appropriate activities, but it is the students who lead the learning. The activities allow all students to engage with the learning and are tailored to meet the needs of individual students. This might include accommodating a special educational need or allowing different academic abilities within a class to access the learning at different points and all make good progress.

In university lectures, the learning experience is very different. Lectures are much more varied and dependent on the lecturer and their preferred style. Material may be presented via a PowerPoint presentation, on overhead projector slides or with written notes on a whiteboard. Most lectures are accompanied by handouts covering the key points, although students may still be required to make their own notes instead.

The large audiences typical in most first year undergraduate lectures mean that the student-led learning and frequent student-teacher interaction common in schools is simply not possible. However inspirational these lectures might be, they are often a one-way transmission of information from lecturer to students. The best lecturers break the presentation up with problems or discussion points to allow for peer interaction, but even then feedback to the lecturer from individual students is pretty unlikely. One way of encouraging this interaction in large group lectures is through the use of electronic voting systems.6 By carefully writing questions that probe the students' understanding, lecturers can gain feedback on the level of progress being made and can identify common student misconceptions. Combining electronic voting with peer discussion or 'contingent teaching' would allow the lecture to become less of a one-way transmission, and more student-led and engaging.7

Bringing it home

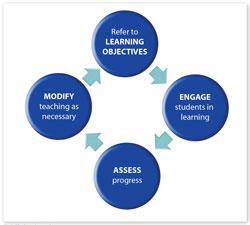

Arguably the most important element of a good lesson is an effective plenary activity, which allows the students and the teacher to refer back to the learning objectives and reflect on whether they have all been met. Often some objectives will remain unfulfilled, but good teachers use this information to inform future planning.

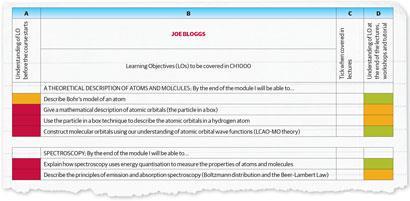

At university, this reflection and assessment of learning occurs in a separate session, often in the form of a workshop, tutorial, laboratory class or indeed personal reflection by the students. This makes it more difficult for the lecturer to identify whether the learning has taken place, and instead the onus is on the student to identify their own areas of weakness and address them. For many students, this is perhaps the biggest challenge of the transition to university study. Self-assessment exercises(fig 3) that encourage students to reflect on their learning are useful for supporting this transition, but at some stage this scaffolding must be removed.

A year as an RSC School Teacher Fellow

Catherine was an RSC School Teacher Fellow, funded by the national HE STEM Programme from 2011 to 2012. She spent a year away from her teaching role at John Cleveland College to be based at the University of Leicester, where she carried out research looking at the transition from secondary school to undergraduate chemistry.

During her year, Catherine investigated how university lecturers received feedback from their students, developed a collection of A-level practical activities to help prepare A-level students for university level chemistry,8 and established a Teacher Development Group for teachers and university staff from the East Midlands Region.

The fellowship scheme allowed secondary school chemistry teachers to be seconded to work in university chemistry departments to share with academics the benefit of their teaching experience, their knowledge of the curriculum, and help them understand the experiences and abilities of incoming undergraduate students.

You can read more about Catherine's year as an RSC School Teacher Fellow on the Fellowship Down blog on MyRSC.9

On the same team

Educators on both sides of the transition need to be aware of the challenges students face on entering higher education. By gradually removing some of the dependence on exam board specifications and teacher-controlled learning at school level, teachers can actively encourage students to develop the all-important independent study skills that they will need to succeed at university.

In turn, university lecturers can help the students adapt to the change in learning style by explicitly stating the main learning points in a lecture, linking this with content covered in workshops, tutorials and lab classes, and encouraging students to reflect on their own learning.

Schemes such as the School Teacher Fellowship can play a significant role in helping those from secondary education appreciate what their students experience on entering higher education, and perhaps assist their students in the transition. It is in the interests of all parties - students, school teachers, and university lecturers - that channels of communication between schools and HE exist to allow examples of best practice and experience to be shared, and help students make this next step on their educational journey as smoothly as possible.

Catherine Smith is a chemistry teacher at John Cleveland College, Hinckley, UK

References

- J Beere, The perfect (OFSTED) lesson. Carmarthen, Wales: Independent Thinking Press, 2011

- J Boniface, D Read and A E Russell, New Directions in the Teaching of Physical Sciences, 2011, 7, 31 (http://bit.ly/WK2f75)

- Education in Chemistry, September 2012, p22 (Jump-starting lectures)

- School inspection handbook, Ofsted, p36, December 2012 (http://bit.ly/1443LXe)

- Improving science in colleges: a survey of good practice, Ofsted, p16. October 2011 (http://bit.ly/1443WSh)

- S P Bates, K Howie and A St J Murphy, New Directions in the Teaching of Physical Sciences, 2006, 2, 1 (http://bit.ly/WK2u24)

- S Draper, Using EVS at Glasgow University c.2005. (accessed October 2012) (http://bit.ly/WK2Khu)

- Education in Chemistry, November 2012, p9 (http://rsc.li/WK3GCz)

- Fellowship Down, MyRSC (accessed January 2013) (no longer available)

No comments yet