Follow the seven steps of live drawing to help your students remember

In 1991, psychologists Richard Anderson and Richard Mayer taught study participants how a bike pump works. Following the instruction, they gave the participants a series of questions designed to test their understanding of how bike pumps work. The participants were taught in one of several different ways – using just words, just pictures, words then pictures or words and pictures simultaneously. The researchers found that participants who were given the words and the pictures simultaneously understood the material far better.

The bike-pump experiment was designed to test Allan Paivio’s dual coding hypothesis, which says that verbal and visual memories are stored differently in long-term memory. Richard Mayer and Richard Anderson wanted to extend that idea to look at how verbal and visual information is processed when someone learns something new. Working memory is restricted – limited to just a few items. In most teacher-facing situations working memory is treated as one entity, with a limited amount of space. If too much material enters the working memory, it doesn’t all fit and learning doesn’t occur.

That model is an oversimplification and cognitive scientists believe that working memory is split into two parts. One part is the phonological loop and deals with language, whether it be reading, writing, speaking or listening. The other component is the visuo-spatial sketchpad, which deals with images – icons, pictures and videos. Both components are limited to a number of items and work as separate channels, effectively doubling the overall number of items that can be held in the working memory. Although it’s not the case that the working memory capacity literally doubles, in the words of cognitive scientist Paul Kirschner in Caviglioli, 2019: ‘according to dual coding theory, if the same information is properly offered to you in two different ways, it enables you to access more working memory capacity. This means that you can benefit from access to both visual and verbal memory capacity’.

In the bike-pump experiment, the group that had both words and images at the same time understood the material the best because they could use both working memory channels to process information. Mayer then spent 30 years investigating which conditions with which different media simultaneously resulted in better learning. This phenomenon is now known as the multimedia effect. The theory and conceptual model that lies underneath this – how the two different components in working memory function simultaneously – is called dual coding.

Putting it into practice

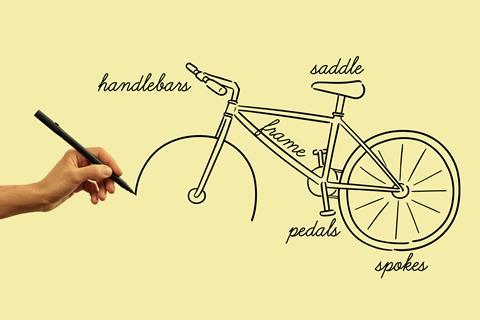

In the classroom, dual coding can be used to great effect. Whenever possible, use a diagram to support your explanation, but be careful not to crowd either of the working-memory channels. If you have words on your diagram and accompany that with a verbal explanation, then you will be filling up the phonological loop with redundant information: you don’t need the words to be written and spoken. Instead, whenever you are trying to take advantage of the multimedia effect try a live drawing approach:

- Start with a blank canvas (ie an empty board).

- Start drawing the diagram, explaining aloud as you go.

- Then add your label to the diagram silently.

- Allow students to read it.

- Bring your students’ attention back to you, and start drawing the next section.

- Explicitly gesture and point to the bits you want students to look at while you are explaining eg by saying ‘look at this’.

- Repeat the cycle until your diagram is complete.

You can also use dual coding to illustrate how the content is organised and how different components relate to each other. You could use a flow diagram to show how fractional distillation works, or a decision tree to help students work out electrolysis products. Bloggers Pritesh Raichura and Rosalind Walker show how you can use a range of visual techniques to help your students organise and categorise information.

However, a random image on a slide isn’t going to help students with dual coding unless it is directly tied to the material. You have to keep your students’ attention fixed on the flow of your explanation. Also be wary of the difference between aesthetics and dual coding. Making your work attractive may be important, but it isn’t dual coding unless it helps your students to understand and remember content.

In short, use a visual representation to support your verbal explanations as often as you can. Avoid crowding your students’ working memories and be sure to direct their attention to where it needs to be.

No comments yet