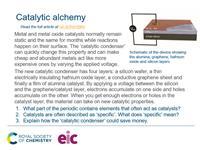

Find out how a catalytic condenser is charging metals, producing speedier catalysts

US scientists have designed a new instrument that can fine-tune the properties of a catalyst. The catalytic condenser can make cheap and abundant metals behave like more expensive ones by simply varying the applied voltage. With the new device, it’s now also possible to bypass the ‘speed limit ’ that governs each catalyst, opening up new opportunities in energy research.

Catalysts are typically metals and metal oxides that are static. They remain the same for months and years while reactions take place on their surfaces. These catalysts have inherent limits: the speed of their reactions and their product selectivity.

Put this in context

Add context and highlight diverse careers with our short career videos showing how chemistry is making a difference and let your learners be inspired by women helping to fix the future, such as Florence, chief technology officer and co-founder of a sustainable solutions company.

The new catalytic condenser allows electrons to be added and removed from a material’s surface at high speed. Catalysts can now be rapidly designed via electronic dials, rather than expensive, slow, iterative synthesis, characterisation and testing.

The device has four key components. Starting with a silicon wafer, the researchers first grew a thin, electrically insulating hafnium oxide layer on it, then added a conductive graphene sheet and finally deposited the catalyst itself – in this case, an alumina film. By applying a voltage difference between the conductive silicon wafer and the graphene/catalyst layer, electrons accumulate on one side and holes accumulate on the other. When you get enough electrons or holes in the catalyst layer, the material takes on new catalytic properties.

Read the full story in Chemistry World.

A one-slide summary of this article with questions to use with your 14–16 students: rsc.li/3MKXTeH

Downloads

EiC starter slide New catalysts

Presentation | PDF, Size 0.15 mbEiC starter slide New catalysts

Presentation | PowerPoint, Size 0.24 mb

No comments yet