Tips and suggestions to help you make the most of ‘In search of solutions’ activities

In search of solutions is a collection of problem-solving activities, written by teachers for teachers. Tried and tested in classrooms, the activities are designed to engage learners in small group work and highlight the fun of chemistry.

What’s on this page

‘In search of solutions’ at a glance

The resources from In search of solutions are suitable for a variety of contexts, including:

- Everyday lessons, to enhance curriculum topic teaching

- End of term activities

- Science clubs

- Outreach events

The activities focus on problem-solving, and can be used to:

- Improve understanding of key concepts by asking learners to apply their acquired knowledge

- Assess learners’ understanding of their work

- Develop social and communication skills by working in teams

- Build confidence and aid motivation

Many of the activities lend themselves to interesting and different ways of presenting results, providing alternative options for learners to report on their work.

Setting up the activities

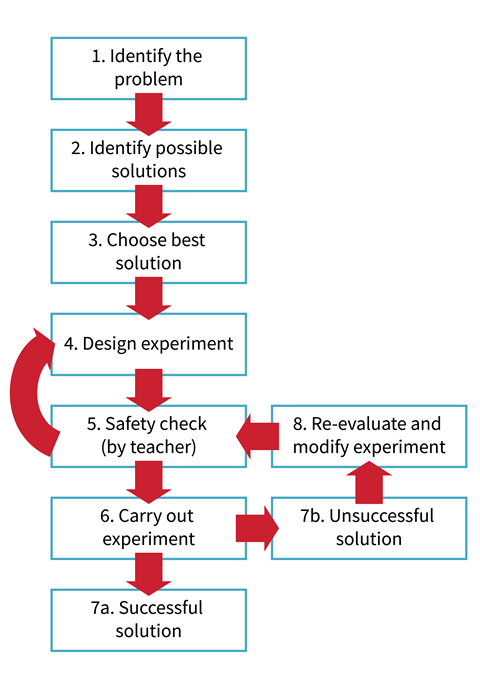

The teachers’ notes for each activity provide an indication of some of the approaches used by learners and teachers when tackling the different problems. (However, it is wise to keep an open mind and to encourage lateral thinking.) When using problem-solving in the classroom, try to ensure that learners don’t change too many variables at once, and instead adopt a step-by-step approach.

Safety should be paramount and it is essential to stress the importance of safe working practices. Encourage learners to consider safety aspects when they plan their experiments. Allow time to check learners’ ideas at the planning stage, before they put their plans into action.

Equipment required by all participants can be put out at each work place. Generally, however, choosing suitable equipment or chemicals is part of the problem to be solved, so aim to have a range of items, including distractors, on tables/benches at the side. These should be arranged in a logical way, eg separating chemicals from equipment. Experience also suggests that for experiments requiring everyday, ‘junk’ items it is better to display these separately from non-junk items, such as laboratory equipment.

Problem-solving activities are not meant to be carried out by individuals, so learners should be organised into groups the size of which will vary depending on the situation. We suggest groups of three or more. However, if the size of the group gets too big, too many people sit around, without having ‘hands-on’ experience. Through discussion, brainstorming and the sharing of ideas and tasks, learners will be ready to take up the challenge provided by the experiment – as a result they will get a feel for what it is like to work in a scientific team.

The problem-solving process

How to assess problem-solving activities

When assessing problem-solving activities, the aim of the activity should be carefully considered.

Assessing projects involves both objective and subjective decisions. It is important to ensure that the project is carried out in a purposeful way; that both the problem and the relevant scientific and technological principles are understood; that a range of alternatives are considered; and that the experimental programme reflects the information collected. It is also necessary to consider how the experimental data was collected, displayed and finally what conclusions were drawn.

Equally important are subjective factors such as ingenuity, curiosity, novelty, enthusiasm, commitment, perseverance, team work, practical ability and an aesthetic sense. Remember that problem-solving activities have been developed to encourage learners to take part in scientific pursuits in an encouraging way. We should expect scientific rigour, relevant to age and ability, but at the same time the activity should be enjoyable.

Problem-solving activities can enrich and complement other teaching approaches. Not all the factors will need to be included for each activity and you will need to choose those most relevant. To avoid misunderstanding, it is worth explaining to learners the basis of the how projects will be assessed and how marks will be awarded. Criteria for which marks could be awarded include:

- Understanding the problem

- Use of the scientific method

- Collection of information

- Consideration of alternative procedures

- Experimental design

- Practical work

- Recording information

- Interpretation/critical assessment of results

- Success in solving the problem

- Suggestions for further work

- Co-operation, team work (if relevant)

- Originality, novelty and ingenuity

- Curiosity and inquisitiveness

- Aesthetic sense

- Perseverance

Decide which to use, how they should be weighted and whether any other factors need to be taken into account.

Health and safety

Safety can be a concern in open-ended problem-solving activities, as you cannot always anticipate what a participant will do. Indeed, some of the best solutions during trials of these problems were the unexpected ones.

Teachers need to be particularly vigilant during practical problem-solving activities, especially when chemicals are involved. A higher degree of supervision is needed than in activities which have more closed outcomes.

To help address these issues, in general terms, the more unusual the activity, the less hazardous are the chemicals suggested for use.

Learners must be encouraged to take a responsible attitude towards safety, both their own and that of others. A statement to this effect should appear prominently in the instructions for the problem. When planning, learners should always include safety as a factor to be considered. Plans should be checked by the teacher before implementing them (unless chemicals and equipment are so constrained as to make that unnecessary). Remember, however, you are not checking whether it will work, but whether it is safe. Always insist upon eye protection. Even if a learner claims to be still thinking, the one on the opposite side of the room may not be!

Read our standard health and safety guidance and carry out a risk assessment before running any live practical, referring to SSERC/CLEAPSS Hazcards and recipe sheets.

Downloads

Index and background

PDF, Size 65.81 kbIndex of activities and junk list

PDF, Size 0.34 mb

Additional information

This article is adapted from P. Borrows, K. Davies and R. Lewin, in In search of solutions, ed. K. Davies, Royal Society of Chemistry, 1990.

No comments yet