Build evaluation into every step of practical work to help your students think and work scientifically

Working scientifically skills are the basis of our science teaching. We can fill our students’ heads with facts, but this alone will not produce the next generation of scientists. Our students need to be able to think scientifically and work scientifically.

Being able to evaluate their practical work is an essential skill. It is transferable to many aspects of life, including evaluating information from advertising, the media and social media.

Evaluation is a higher order thinking skill and one many students find difficult

In our science teaching, evaluation is often the skill that is tagged on at the end of an investigation. Students have planned and carried out their experiment, recorded results, analysed them, formed a conclusion and only then do they evaluate their work. Students should evaluate their investigation as they do it.

Evaluation is a higher order thinking skill and one many students find difficult. Students are required to think objectively about work they have been subjectively involved in. A common response from students in explaining errors or unexpected results is that they may have made a mistake.

Download this

Evaluating experiments worksheet, for age range 14–16

Use this resource to take learners step by step through the evaluation process to improve their working scientifically skills.

Download the teacher notes, with example answers, as MS Word or pdf, student worksheet as MS Word or pdf and scaffolded student worksheet as MS Word or pdf.

Download this

Evaluating experiments worksheet, for age range 14–16 years

Use this resource to take learners step by step through the evaluation process to improve their working scientifically skills.

Download the activity from the Education in Chemistry website: rsc.li/3ZVm29t

Helping students develop evaluating skills

How do we enable students to evaluate an investigation while it is in progress? This strategy is most useful when applied to a student’s own investigations which involve them forming a hypothesis and a plan. Investigations such as those based on rates of reaction, electrolysis and titrations provide good opportunities. Practicals which repeat experiments done many times before to illustrate a scientific idea may be of limited use.

At the planning stage, students must consider whether their method will provide valid data relevant to their hypothesis and investigation. This includes identifying the dependent and independent variables and the variables they need to control. There may be variables that students cannot control, such as room temperature. Identifying these may indicate sources of error in any data collected.

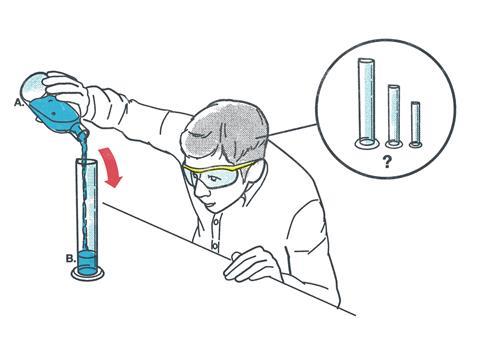

Students need to be aware that the choice of measuring apparatus they use will affect the accuracy of their data. Due to manufacturing methods, school laboratory glassware used for measuring is rarely 100% accurate. Most glassware has its uncertainty printed on it. For example, a 100 cm3 measuring cylinder usually has an uncertainty of ±0.5 cm3, whereas a 10 cm3 measuring cylinder usually has an uncertainty of ±0.1 cm3. Encourage post-14 students to select apparatus to give the smallest error for the amounts they are measuring. Post-16 students can calculate the percentage errors.

Errors in data may result from methods used. Heat loss in calorimetry experiments and those involving exothermic and endothermic reactions is one example. There may be procedural errors due to the way students carried out their experiments. Post-16 students can identify errors as random or systematic.

Recommended reading and resources

- Read an article about students evaluating experiments and download the accompanying worksheet comparing different methods and a card sort on improving accuracy and reliability.

- Link to other skills, such as developing a hypothesis and planning, with the candle burning investigation for learners aged 11–16.

- Find ideas and activities to help your students understand accuracy and error.

- Highlight chemistry careers that use evaluation skills, for example this video job profile of Saba, principal air quality consultant.

- Help students evaluate experiments with a worksheet comparing different methods and a card sort on improving accuracy and reliability: rsc.li/3Lv4vRN

- Link to other skills, such as developing a hypothesis and planning, with the candle burning investigation for learners aged 11–16: rsc.li/3LcOwHy

- Find ideas and activities to help your students understand accuracy and error: rsc.li/3YLaxk7

- Highlight chemistry careers that use evaluation skills, for example this video job profile of Saba, principal air quality consultant: rsc.li/3FcSI6u

Evaluating the conclusion

Students can now use their awareness of the procedures and apparatus used to evaluate their conclusion. There are many questions to ask and answer.

Did they identify and dismiss any anomalous results? Have they used a suitable range of values for the independent variable? An investigation into the effects of temperature on a rate of reaction will produce more valid results if students use a wide range of temperatures, such as 10°C to 60°C, rather than investigating a narrower range of temperature. Was there time to do repeats and calculate an average result?

What was the biggest source of error? Was it due to the apparatus used, the method used or the students themselves? What are the limitations of their investigation? If students conclude that the rate of a certain reaction increases with increasing temperature, is this relevant to temperatures above and below the range investigated?

Are their findings reproducible? Will another group of students using the same method and apparatus come to the same conclusion?

Most exam specifications require students to suggest improvements to the procedure and apparatus used in an investigation. Using the worksheet (above) as a checklist, students can evaluate their investigation as they are doing it. Reviewing their comments can inform suggestions for improvement.

Most exam specifications require students to suggest improvements to the procedure and apparatus used in an investigation. Using the downloadable worksheet as a checklist, students can evaluate their investigation as they are doing it. Reviewing their comments can inform suggestions for improvement.

Getting your students to evaluate their investigations while they are in progress will improve the quality of their practicals and equip them with an essential skill for their science courses and far beyond.

This article is part of our Teaching science skills series, bringing together strategies and classroom activities to help your learners develop essential scientific skills, from literacy to risk assessment and more.

No comments yet