Try this class experiment to carry out the electrolysis of various solutions and investigate the products formed

In this practical, students get the chance to practise doing electrolysis with a range of solutions, identifying the products that form at the electrodes. They should be able to link their practical experience with theory and learn how to construct simple ionic equations.

The class experiment is best done by students working in pairs or threes. There are plenty of tasks for each member of the team to complete.

It should be carried out in a well-ventilated laboratory as significant amounts of toxic chlorine, bromine and iodine can be produced in some cases, as well as highly flammable hydrogen.

Equipment

Apparatus

- Eye protection

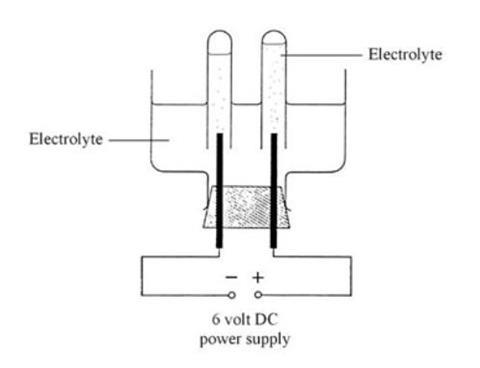

- Electrolysis apparatus (see note 1, and the diagram below)

- Graphite electrodes, about 5 mm diameter, x2 (see note 2)

- Large rubber bung to fit electrolysis cell, with holes to carry the graphite electrodes

- Small test tubes to fit over the electrodes, x2

- DC power supply, 6 V

- Small light bulb in holder, 6V 5W (optional)

- Leads and crocodile clips

- Wooden splints

- Small pieces of emery paper

- Strips of universal indicator paper

- Disposable plastic gloves

- Clamp and stand

Chemicals

Access to the following solutions, all approximately 0.5 M concentration (see note 3):

- Aqueous potassium bromide

- Aqueous sodium iodide

- Aqueous calcium nitrate

- Aqueous zinc chloride (IRRITANT at this concentration)

- Aqueous copper nitrate

Equipment notes

- The electrolysis apparatus shown below can be purchased ready-made. Alternatively, it can be made from thick glass tubing of 8–10 cm diameter, professionally cut into lengths of about 12 cm. A suitable glass bottle, with a wide-necked top and its base cut off, could be used instead (as shown in the diagram). The graphite rods should be well sealed into the holes, 2–3 cm apart, of the rubber bung, otherwise the electrolyte may leak onto the external wiring, causing it to corrode. Once made, this apparatus should last for several sessions, but the graphite rods tend to erode away quite quickly, particularly if students use larger than recommended voltages. The rods do eventually become thin and snap fairly easily, but they are cheap enough to replace.

- Once copper(II) nitrate has been electrolysed (preferably last), a deposit of copper will have formed on the cathode. This has to be removed before the cells can be used again. Immersing the plated part of the electrode in a small quantity of 50% concentrated nitric acid (CORROSIVE) in a small beaker can be used to do this. Gloves and eye protection should be worn and the cleaning done in a fume cupboard by a suitably qualified person.

- Depending on the volume of the electrolysis apparatus, each group of students needs enough solution to cover the electrodes plus about 2 cm to enable the full test tubes of liquid to be inverted over the electrodes.

Health, safety and technical notes

- Read our standard health and safety guidance.

- Wear eye protection throughout.

- The experiment should be carried out in a well-ventilated laboratory as it may produce significant quantities of toxic chlorine, bromine and iodine, as well as highly flammable hydrogen.

- Aqueous potassium bromide, KBr(aq) – see CLEAPSS Hazcard HC047b.

- Aqueous sodium iodide, NaI(aq) – see CLEAPSS Hazcard HC047b.

- Aqueous calcium nitrate, Ca(NO3)2 (aq) – see CLEAPSS Hazcard HC019B.

- Aqueous zinc chloride, ZnCl2 (aq), (IRRITANT at concentration used) – see CLEAPSS Hazcard HC108a.

- Aqueous copper nitrate, Cu(NO3)2 (aq) – see CLEAPSS Hazcard HC027B.

- 50% concentrated nitric acid, HNO3 (aq), (CORROSIVE) – see CLEAPSS Hazcard HC067 and CLEAPSS Recipe Book RB061. This is used to clean copper off the electrodes, and is made by slowly adding concentrated nitric acid to an equal volume of water.

- Chlorine, Cl2 (g), (TOXIC) – see CLEAPSS Hazcard HC022a.

- Bromine, Br2 (l), (TOXIC) – see CLEAPSS Hazcard HC015a.

- Iodine, I2 (s), (TOXIC) – see CLEAPSS Hazcard HC054.

Procedure

- Set up a table for results like this:

| Potassium bromide | Sodium iodide | Calcium nitrate | Zinc chloride | Copper nitrate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lamp lights? | ||||||

| Observations | Cathode (–) | |||||

| Anode (+) | ||||||

| Test used for product | Cathode (–) | |||||

| Anode (+) | ||||||

| Identity of products formed | Cathode (–) | |||||

| Anode (+) | ||||||

- Clamp the electrolysis cell and pour in enough of the first electrolyte so that the tops of the electrodes are covered with about 1–2 cm of liquid. Fill the two test tubes with the same electrolyte. Wearing gloves, close the end of each test tube in turn with a finger and invert it over an electrode, so that no air is allowed to enter (see diagram). During electrolysis it may be necessary to lift the test tubes slightly to ensure that the electrodes are not completely enclosed, preventing the flow of current.

- Connect the circuit, and mark the polarity of each electrode on the bung. The circuit should be checked before being switched on.

- Switch on the circuit, then:

- Observe whether or not the lamp lights up.

- Look for the substances produced at each electrode – ie gaseous, solid or in solution.

- Write down results after each observation, not when all the experiments are finished.

- Only carry out the electrolysis for long enough to make the necessary observations. Prolonging the electrolyses unnecessarily causes toxic gases such as chlorine and bromine to be produced in unacceptably hazardous quantities. Switch off the current immediately if this becomes apparent.

- After each electrolysis switch off the current and remove the test tubes from the cell to test any gases present by lifting them slowly in turn to let any remaining solution drain out before closing the end with a finger. Carry out the tests on the gases as instructed.

- (Optional) After removing the test tubes from the cell, quickly pour the liquid down the sink with plenty of water. Wipe a piece of universal indicator paper over each electrode and note any colour changes.

- Wash the cell with plenty of water and dry the outside with a paper towel before fixing it back into position and reconnecting the power supply. It is important to connect the leads according to the polarities marked on the bung.

- Repeat the experiment with each of the other four solutions, trying to keep to the order given in the table. Zinc chloride and copper nitrate should be the last electrolytes tested. This is because they deposit solids on the cathode. If zinc chloride is electrolysed first, the solid deposit on the cathode can be easily removed with a piece of emery paper or dipping the end of the electrode in some dilute hydrochloric acid in a beaker.

Teaching notes

The electrolysis of aqueous solutions, rather than molten salts, is easier and safer for students to do for themselves, Unfortunately the theory is more complicated, because the presence of water complicates what students may decide are the products formed at the electrodes.

More support

Use the animations included in our practical video Electrolysis of aqueous solutions to help learners think about which ions are present in an aqueous solution and what is happening at each electrode.

Ensure that students do not attempt to smell directly any of the halogen fumes produced. It is important that you are aware of any students who are asthmatic or who might have an allergic reaction to these toxic gases. In this context do not allow the electrolyses of the halide solutions to proceed any longer than is absolutely necessary.

When testing for hydrogen or oxygen, the mouth of the test tube can be closed with a gloved finger, and the test tube transported to a central area, where a single naked flame has been set up, well away from the experiments. A supply of spills can also be kept in this area for the tests.

For the hydrogen test, students may well ask why there is little or no ‘pop’ or ‘squeak’. Explain that pure hydrogen – rather than a mixture of hydrogen and air – is being tested if the test tube was full of gas before it was removed.

For the oxygen test, care should be taken that the dampness at the mouth of the test tube does not extinguish the ‘glow’, causing the test to fail.

Once the electrolysis of zinc chloride or copper nitrate has been done, a deposit of metal will have formed on the cathode. This will have to be cleaned before the cell can be used again. These metal deposits can be removed using emery paper. Alternatively, small quantity of 50% concentrated nitric acid (CORROSIVE) in a small beaker can be used to remove the copper, providing gloves are worn and the operation is done in a fume cupboard by a suitably qualified person. Similarly dilute hydrochloric acid will remove the zinc.

Results and conclusions

| Potassium bromide | Sodium iodide | Calcium nitrate | Zinc chloride | Copper nitrate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lamp lights? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Observations | Cathode (–) | Colourless gas | Colourless gas | Colourless gas | Whitish-grey solid deposit | Reddish-brown solid deposit |

| Anode (+) | Orange-brown solution; maybe a little orange coloured gas | Dark brown solution | Colourless gas | Tiny bubbles forming at electrode: very pale green gas, but most dissolves | Colourless gas | |

| Test used for product | Cathode (–) | Gas ignited by burning splint; maybe a ‘squeak’ | Gas ignited by burning splint; maybe a ‘squeak’ | Gas ignited by burning splint; maybe a ’squeak | Powder appearance | Powder appearance |

| Anode (+) | Universal indicator paper turns red and is bleached | Turns starch solution blue/black | Relights a glowing splint | Universal indicator paper turns red and is bleached | Relights a glowing splint | |

| Identity of products formed | Cathode (–) | Hydrogen | Hydrogen | Hydrogen | Zinc | Copper |

| Anode (+) | Bromine | Iodine | Oxygen | Chlorine | Oxygen | |

Notes on the theory

Cathode reactions:

KBr NaI Ca(NO3)2: 2H2O(l) + 2e–→ H2(g) + 2OH– (aq)

ZnCl2 Cu(NO3)2: M2+(aq) + 2e–→ M(s)

Anode reactions:

KBr NaI ZnCl2: 2X–(aq) → X2(g/aq) + 2e–

Ca(NO3)2 Cu(NO3)2: 2H2O(l) → O2(g) + 4H+(aq) + 4e–

For KBr NaI and Ca(NO3)2 it is likely that students will ask why hydrogen is the gas evolved rather than the metal. Students could then be asked to imagine what would happen if one of these metals is formed given that this occurs in the presence of water. The ensuing reaction produces hydrogen as one of the products and the metal hydroxide as the other. Students of higher ability could be introduced to the concept of electrode potentials and be given details of the probable reaction occurring at the cathode shown earlier.

With chlorine in particular and with bromine too students will find that the indicator paper is bleached as well as showing signs of acidity. Iodine usually stains the paper brown.

Some students may ask about the relative volumes of gases produced at the electrodes. While this practical is not designed to investigate this they can be told the following. The volume ratio of hydrogen and chlorine gases produced during the electrolysis of NaCl is actually 1:1. Nothing like this is observed in practice because chlorine is slightly soluble in the aqueous solutions and the gas does not begin to collect until the electrolyte solution has become saturated with it.

Less advanced students could be asked to concentrate on simple observations, eg Is a gas formed? What pH changes occur at the electrodes? The main principle to emphasise is that the conduction of electricity by aqueous solutions is due to the movement of ions (not electrons) and that these travel to the electrodes of opposite charge.

Less advanced students should simply note that:

- The solution around the cathode tends to become alkaline.

- The solution around the anode tends to become acidic.

- Metals low in the reactivity series appear to be deposited at the negative electrode.

- A gas is evolved at the negative electrode if the metal is high in the reactivity series. If appropriate they can be told that this gas is hydrogen.

- Non-metals are formed at the positive electrode: chloride ions produce gaseous chlorine bromide and iodide ions form bromine and iodine respectively which dissolve to form coloured solutions.

- The electrolysis of copper nitrate produces a colourless gas at the positive electrode. If appropriate students can be told that this is oxygen.

Additional information

This is a resource from the Practical Chemistry project, developed by the Nuffield Foundation and the Royal Society of Chemistry.

Practical Chemistry activities accompany Practical Physics and Practical Biology.

The experiment is also part of the Royal Society of Chemistry’s Continuing Professional Development course: Chemistry for non-specialists.

© Nuffield Foundation and the Royal Society of Chemistry

No comments yet