Scientific literacy is a key skill for all learners and Ben Rogers believes it should feature in all science lessons

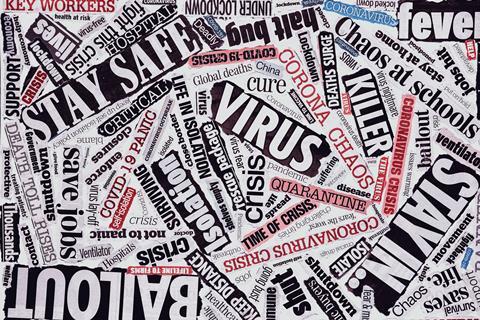

In 2020, we all became experts in viruses: how they reproduce; how they pass from person to person; how to prevent their spread. As time went on, we learned about face masks, alcohol gels and vaccines. We read articles in newspapers and online, becoming experts in exponential graphs and interpreting map data. Reading science articles became a key skill for any informed citizen. I’ve been teaching for 30 years: had I prepared my students, many now in their 40s, to read science articles?

I’ve always believed that teaching science is about literacy. Very few of the students I’ve taught have become scientists, but they’ve all become citizens where scientific literacy is important. But if citizenship isn’t a good enough reason to teach literacy, how about awe and wonder? The more confident and enthusiastic our students become as readers of science, the richer their lives will be. Some may even choose to become scientists.

What is literacy in chemistry?

Literacy is about sharing understanding. The art of reading is to take the words someone has carefully put together and build them into your own mental model. The art of writing is to take an idea in your mind and work out the best choice of words to help your reader construct the same meaning.

If we want our students to read and understand chemistry, they need to practise literacy in their chemistry lessons

The third element of literacy is talk – the iterative cycle of listening and explaining. When students discuss an idea, they are developing their reading and writing. Reading and listening correlate well, as do explaining and writing. So when we support our students to discuss an idea, we are also developing both their reading and writing skills. The reverse is also true: reading and writing develop discussion. The advantage of discussion is, it’s quick. The advantage of reading and writing is that it is slow – our students can read and re-read or write and rewrite.

When we practise one type of literacy in lessons, we are developing all types, but getting a balance is important. What does the research say?

How to teach literacy

In 2021, the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) published their report, Improving Literacy in Secondary Schools. The EEF identified seven principles to support literacy. Their first point (and I think the most important) is to ensure that each subject teaches literacy. If we want our students to read and understand chemistry, they need to practise literacy in their chemistry lessons. The second point is about knowledge: if you want to read about, listen to and discuss chemistry, you need rich chemistry knowledge. The remaining principles discuss how to teach literacy: listening, talking and writing all support better literacy. Breaking complex literacy tasks down into small achievable activities is important too. Finally, recognise that some of your students will struggle with reading in general – your school should implement reading interventions for these students.

In 2021, the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) published their report, Improving Literacy in Secondary Schools (bit.ly/3RJi2qo). The EEF identified seven principles to support literacy. Their first point (and I think the most important) is to ensure that each subject teaches literacy. If we want our students to read and understand chemistry, they need to practise literacy in their chemistry lessons. The second point is about knowledge: if you want to read about, listen to and discuss chemistry, you need rich chemistry knowledge. The remaining principles discuss how to teach literacy: listening, talking and writing all support better literacy. Breaking complex literacy tasks down into small achievable activities is important too. Finally, recognise that some of your students will struggle with reading in general – your school should implement reading interventions for these students.

More resources to support literacy in the science classroom

Discover our latest literacy support resources by key topic. Each set includes:

- reading comprehension

- structured talk activity

- structure strips to support independent writing

- key term support pack, with definitions, accessible glossary, Frayer models and unscrambling definitions.

Find them along with our carefully curated collection of articles and classroom-ready activities to help you embed literacy into your existing lessons.

Discover our latest literacy support resources by key topic. Each set includes: reading comprehension, structured talk activity, structure strips to support independent writing and a key terms support pack, with definitions, accessible glossary, Frayer models and unscrambling definitions worksheet.

Find them along with our carefully curated collection of articles and classroom-ready activities to help you embed literacy in your existing lessons: rsc.li/42ouFMP

Developing literacy in chemistry

Incorporating talking activities in chemistry lessons is a powerful way to practise and develop literacy. Naomi Hennah, former chemistry teacher and now a learning excellence coach, has written several excellent articles to help with this, including using debate in the classroom, talking to develop deeper understanding of practical work and using talk triplets.

Incorporating talking activities in chemistry lessons is a powerful way to practise and develop literacy. Naomi Hennah, former chemistry teacher and now a learning excellence coach, has written several excellent articles to help with this, including using debate in the classroom, talking to develop deeper understanding of practical work and using talk triplets: rsc.li/3RJiqoQ

I am also a big fan of the teacher read aloud model for all students. When the teacher reads short texts aloud to students with good clear prosody, all students, especially those who are weak readers, develop their comprehension. The Faster read project from the University of Sussex has found that reading complex texts (typically fiction) leads to very impressive gains in reading comprehension. I suspect the same would happen with chemistry texts, but there is no research on this.

For writing, I recommend starting with sentences. When you communicate a complex scientific concept in a single sentence, you improve your scientific comprehension. My favourite teaching tool for this is using ‘but, because, so’ sentence starters. For example, a sentence beginning, ‘In a liquid, the particles are free to move around, but …’ could be completed by students with ‘they cannot separate easily’. Even if the exam board does not insist on full sentences, supporting your students to write better sentences is one of the best ways to develop thinking and deeper understanding. For more on this, look out for my follow-on article about writing strategies.

No comments yet