How including women scientists’ work can help achieve parity and inspire a generation to study chemistry

In recent years, there has been a significant change in the way we think about gender equality in education. As educators, we are no longer debating how big or small the gender gap is; instead, we are taking action to close it and considering how best to do this.

Despite this positive shift, only 24% of roles within the STEM workforce are occupied by women. Although the number of women working in STEM fields has increased in recent years, taking the total number over the one million mark for the first time, men still occupy three quarters of STEM roles.

Moreover, statistics show that girls are still less likely than boys to pursue STEM subjects when they are no longer compulsory. According to UCAS, from 2015 to 2019 there was an increase of only 1000 female graduates in core STEM subjects. So progress is still slow. And yet there seems to be no reasonable justification for this, as girls are outperforming boys across all A-level STEM subjects, with 52.2% awarded A or A* across all subjects, compared to 49.3% of boys.

Despite this positive shift, WISE found that only 24% of roles within the STEM workforce are occupied by women. Although the number of women working in STEM fields has increased in recent years, taking the total number over the one million mark for the first time, men still occupy three quarters of STEM roles.

Moreover, statistics show that girls are still less likely than boys to pursue STEM subjects when they are no longer compulsory. According to UCAS, from 2015 to 2019 there was an increase of only 1000 female graduates in core STEM subjects. So progress is still slow. And yet there seems to be no reasonable justification for this, as girls are outperforming boys across all A-level STEM subjects, with 52.2% awarded A or A* across all subjects, compared to 49.3% of boys.

Proper representation

There is no doubt that we need to harness the talent and potential of girls to secure a strong STEM workforce for the future, particularly as the UK is now facing a STEM labour shortage. There are several reasons behind the slow progress in increasing the number of women pursuing STEM careers, but perhaps the most important factor is the lack of representation. Girls are unlikely to have the confidence to pursue a career in science when there is an ongoing absence of positive representation of women in science subjects. Increasing the visibility of women in the science curriculum can provide a huge source of inspiration for young girls and give them the confidence to explore careers in STEM.

There is a tacit agreement in the curriculum that the ideas of science are more important than the people who discovered them: the people are history; the content is science. However, while we have all heard of Newton and Galileo, Darwin and Mendeleev, how many would recognise the names Franklin, Hodgkin or Bell Burnell? And why is this important?

Celebrating and empowering women

At Paradigm Trust – a not-for-profit educational trust with schools in Ipswich and Tower Hamlets – we want all our pupils to see themselves represented within our curriculum. We aim to improve the representation of women in science lessons and to usualise women in science; in other words, showing women in science as often as possible, but without drawing attention to the fact that the scientists are women. The focus should be on the scientific achievements of the individual, not their gender. This approach helps reduce the risk of othering women and, instead, empowers them through the celebration of their successes.

At Paradigm Trust – a not-for-profit educational trust with schools in Ipswich and Tower Hamlets – we want all our pupils to see themselves represented within our curriculum. We aim to improve the representation of women in science lessons and to usualise women in science; in other words, showing women in science as often as possible, but without drawing attention to the fact that the scientists are women. The focus should be on the scientific achievements of the individual, not their gender. This approach helps reduce the risk of othering women and, instead, empowers them through the celebration of their successes.

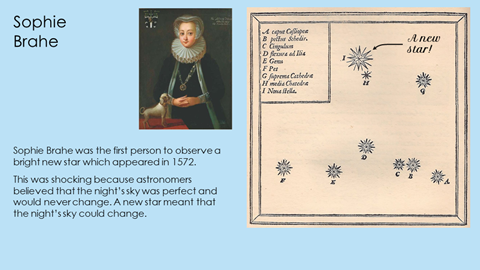

In practice, we use simple techniques to ensure our teaching materials highlight female scientists, both past and present, when covering key topics. As an example, here is a short hook to a lesson that would take less than five minutes (first slide included here):

Pupils read the introductory slide, then the teacher briefly discusses the science. Unless a pupil raises it, the scientist’s gender is not mentioned specifically. A timeline is used to point out other historic events around the time (the Tudors and Shakespeare make for good reference points). Following the short description of the scientist’s contribution, pupils predict what the main part of the lesson will be about.

We use a similar approach to usualising contemporary women scientists, based on excellent work by NUSTEM at the University of Northumbria. NUSTEM sees teachers as a key influence on young children’s career aspirations, and has developed resources about STEM careers to broaden those aspirations – not least among girls. Their career slides show counter-stereotypical images and list key attributes of a person in the job, and can be used briefly (for two to three minutes) between the start and the main body of a lesson.

We use a similar approach to usualising contemporary women scientists, based on excellent work by NUSTEM at the University of Northumbria. NUSTEM sees teachers as a key influence on young children’s career aspirations, and has developed resources about STEM careers to broaden those aspirations – not least among girls. Their career slides show counter-stereotypical images and list key attributes of a person in the job, and can be used briefly (for two to three minutes) between the start and the main body of a lesson.

Weaving equality into lessons

This approach helps to address some issues, but is not a solution. The big challenge is to weave equality throughout lessons while still teaching the assessed curriculum. It is not in the best interest of the student to point them to opportunities but then fail to prepare them adequately for the exams they need to achieve their goals.

It’s vital to challenge gender stereotypes in early years education

Paradigm Trust also supports its teachers in challenging pupils when comments or class materials present a biased or unbalanced view of science and scientists. In a recent science lesson on bacteria a young student asked: ‘Who invented the first vaccine? Was he British?’ The teacher addressed the unconscious gender bias in the question (in a sensitive way), and then celebrated the work of Sarah Gilbert on the first Covid-19 vaccine at Oxford.

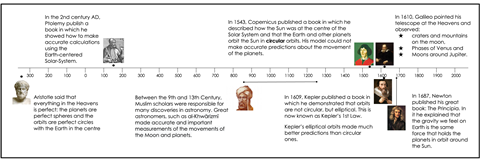

Not only do we challenge these gender biases whenever they arise, but we also actively encourage students to reflect on the gender imbalance in the field of science. So, when using a history of astronomy timeline, for example, teachers are encouraged to pause the lesson for a short discussion by asking: ‘Where are all the women?’ By keeping gender equality in mind, our teachers are getting better at spotting and challenging potential misconceptions and prejudices as they arise.

Gender stereotypes in schools

We know there is still a problem with representation and gender stereotyping in schools. A 2021 report from the Fawcett Society highlighted how gender stereotypes continue to impact negatively on the life chances of young girls. Academic research reveals that both the school environment and practitioners continue to separate boys and girls unnecessarily, through language and segregation.

The evidence suggests that, in many cases, children are still encouraged to engage in behaviour that is stereotypically expected – physical play for boys and caring tasks for girls. This can influence children’s interest and success in different subjects, but also deter girls from following subjects they view as requiring them to be really, really smart. The influential ASPIRES project finds that by the end of primary school many pupils have decided that a career in the sciences is not for them, and that they don’t change their minds by the time they leave school.

This is why it’s vital to challenge gender stereotypes in early years education. At Paradigm Trust, we try to do this through stories and literature. There is evidence to suggest that using counter-stereotypical reading material can reduce gender-stereotyped views and behaviours and improve well-being. The school library, therefore, is a great place to begin introducing positive representation, perhaps using a list like this for inspiration: 29 children’s books about female scientists. Books such as Women in science by Rachel Ignotofsky and Look up! by Nathan Bryon provide young girls with the perfect role models to grow up with, while inspiring a love of science.

Find out more

Discover more women working in chemistry such as chief technology officer and co-founder of a sustainable solutions company, Florence, who is helping to reduce the world’s reliance on petroleum.

We know there is still a problem with representation and gender stereotyping in schools. A 2021 report from the Fawcett Society highlighted how gender stereotypes continue to impact negatively on the life chances of young girls. Academic research reveals that both the school environment and practitioners continue to separate boys and girls unnecessarily, through language and segregation.

The evidence suggests that, in many cases, children are still encouraged to engage in behaviour that is stereotypically expected – physical play for boys and caring tasks for girls. This can influence children’s interest and success in different subjects, but also deter girls from following subjects they view as requiring them to be really, really smart. The influential ASPIRES project finds that by the end of primary school many pupils have decided that a career in the sciences is not for them, and that they don’t change their minds by the time they leave school.

This is why it’s vital to challenge gender stereotypes in early years education. At Paradigm Trust, we try to do this through stories and literature. There is evidence to suggest that using counter-stereotypical reading material can reduce gender-stereotyped views and behaviours and improve well-being. The school library, therefore, is a great place to begin introducing positive representation, perhaps using a list like this for inspiration: 29 children’s books about female scientists. Books such as Women in science by Rachel Ignotofsky and Look up! by Nathan Bryon provide young girls with the perfect role models to grow up with, while inspiring a love of science.

Constant vigilance and determination by all teachers and school leaders is a necessity to progress towards equality. However, by ensuring that teaching materials represent the significant contributions that women have made to the advancement of science, teachers can raise the aspirations of young girls and increase the likelihood they will pursue a career in STEM. If they see it, they’ll believe it.

Frances Goodship is a primary school teacher, subject lead and pedagogy lead at Solebay Primary Academy (Paradigm Trust) and Ben Rogers leads on curriculum, pedagogy and assessment for KS1–3 at Paradigm Trust

Top image, clockwise from bottom left: Isaac Newton (© Nicku/Shutterstock), Jocelyn Bell Burnell (© SSPL/Getty Images), Charles Darwin (© Everett Collection/Shutterstock), Rosalind Franklin (© Donaldson Collection/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images), Marie Curie (© Everett Collection/Shutterstock), Dmitri Mendeleev (© Mondadori/Getty Images), Emmanuelle Charpentier (L) Jennifer Doudna (© Miguel Riopa/AFP/Getty Images), Dorothy Hodgkin (© Mondadori/Getty Images)

No comments yet