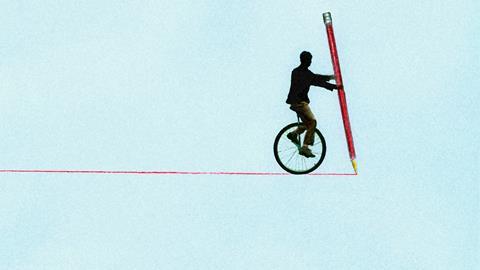

‘Could do better’ reports Kristy Turner when she reflects on science educators’ ability to transfer skills, as well as knowledge

The literature tells us that graduates are lacking in communication skills, commercial awareness, analysis and decision-making skills, passion and literacy (ie good writing skills). Newspapers report that graduates are immature and lacking resilience and self-management skills, while social media feeds are full of stories suggesting that under 25s can’t read the time on a standard clock face and are anxious making and receiving telephone calls.

The transition from the world of education to the world of work is as important as any of the transitions students make, and yet we’re still not managing it very well. We have made a lot of progress in ‘onboarding’ students into our degrees in first year. What about ‘offboarding’ them at the end of their studies?

Reflecting on our own profession, what makes us good at our jobs? As educators, our jobs are firmly centred around a core of knowledge, but knowledge alone doesn’t make us successful. We need the skills to be able to use that knowledge to make it meaningful to our day-to-day tasks and a whole extra set of non-subject specific skills as well. No educator is an island, no matter what our context; in schools, colleges and universities, our jobs are team based and hopefully collaborative. We have to be tolerant, resilient, excellent communicators in a range of media and get along with everyone from the caretaker to the headteacher.

The status of knowledge

Knowledge is the current education buzzword. School curriculums have to be knowledge rich in order to be accepted by the current trendsetters and influencers of the education world. Of course, undergraduate degrees have been knowledge rich since their inception. A chemistry degree comprises a huge amount of content and much of it is assessed in exams. The acquisition of new chemical knowledge has the very highest status, everything else is cast in its shadow. But knowledge is always expanding, we have more than enough content to fill an entire four-year degree and then some. We cannot simply keep stuffing more and more content into students’ heads. Our obsession with knowledge and the status it has gained means there is a very real risk of undermining the value of skills in the overall package and sending our students out into the world ill-equipped for the challenges of work (or even further study).

Most universities have skills modules in their undergraduate programmes. These are varied and include skills like information retrieval, the use of specific software packages, academic and other forms of writing and presentation skills. My experience in the chemistry education community and as someone who teaches on a skills module tells me these courses are seriously underappreciated by students. Attendance is poor, engagement with assessments patchy – the whole process is frustrating for everyone concerned. However, on mature reflection, maybe we only have ourselves to blame?

How did we end up here?

Those in charge of designing programmes of study, both in school curriculums and university degrees, are themselves successful learners – their security lies in knowledge. Academics in higher education institutions were themselves successful at ‘knowing lots of stuff’ and to join this club others (our students) also need to know lots of stuff. This ‘knowing lots’ attitude is passed onto students and so the cycle continues. Degrees are designed around the chemical concepts, with skills tagged on the side.

Perhaps you think it is the responsibility of the students themselves to go and seek out opportunities to develop skills and specific teaching of skills has no place in a chemistry degree. This is a dangerously divisive attitude. A chemistry degree is labour intensive, with typically 25+ hours of contact time a week. Add in the independent study, completing lab reports and tutorials, preparing for exams and completing coursework and it is not unusual for students to be working 40-50 hours a week. So a chemistry degree is pretty much a full-time job. Students can gain hugely beneficial skills from volunteering, being involved in sports clubs and student societies and completing internships. However, these may not be accessible to less advantaged students. Quite simply, if you’re having to take on paid employment to help pay the rent or you’re rushing off from lectures to relieve the childminder then those opportunities are pretty much closed to you. Surely we can do better than to perpetuate disadvantage?

I don’t pretend to have all the answers, but let’s keep the skills discussion a high priority. If we were to write ourselves a report card for graduate skills, it would surely say ‘could do better’.

4 readers' comments