Why has science attainment decreased in England but stayed the same in Ireland – and what can educators learn from it?

Run by the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement, the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) compares the performance in maths and science of pupils aged 9–10 and 13–14 every four years. More than 60 countries participated in TIMSS 2019 – including England and Ireland, who have taken part in every TIMSS since the first study in 1995 – with results providing valuable information on performance trends. Indeed, the 2019 performance of both year 9 students in England and second year pupils in Ireland in science drew out some interesting insights.

Decline in England

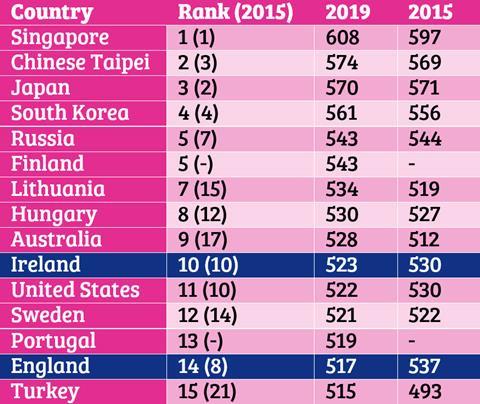

In both maths and science, English pupils performed well above the TIMSS centre-point of 500 (the centre-point has provided a constant reference since 1995). However, compared to 2015, performance has decreased significantly in science: scores had remained stable between 1995 (533) and 2015 (537), but the most recent score of 517 is the country’s lowest ever since the study began.

The result means that England has fallen from 8th to 14th in the TIMSS rankings for secondary science. (In comparison, maths performance improved between 1995 and 2015, and was static between 2015 and 2019 – putting England in 12th place internationally, down from 11th.)

The science assessment includes biology, chemistry, physics and earth sciences. Looking at individual science subjects, the study showed that English pupils performed in line with the average score for science in biology, physics and earth science – but the score in chemistry was slightly lower (scoring 512 compared to the average of 517). Ireland, Australia and the US also had significantly lower scores in chemistry compared to their overall science averages. In the top five countries for science, chemistry scores were only significantly above the overall science average in Chinese Taipei, Russia and Singapore, but not in Japan and the Republic of Korea.

The reasons behind the drop in England’s science performance are unclear. The report on TIMSS for the Department for Education (DfE) by researchers from the UCL Institute of Education suggests it may be because many schools start GCSEs in year 9 – which could shift focus on science content – or because teachers are placing less emphasis on science in primary schools after the move in 2009 to drop formal KS2 tests in science.

The reasons behind the drop in England’s science performance are unclear. The report on TIMSS for the Department for Education (DfE) by researchers from the UCL Institute of Education suggests it may be because many schools start GCSEs in year 9 – which could shift focus on science content – or because teachers are placing less emphasis on science in primary schools after the move in 2009 to drop formal KS2 tests in science (LINK).

Steady in Ireland

Irish students, on the other hand, have been performing at a relatively high level, especially in maths. Their 2019 performance has remained stable, with an overall score for science and maths well above average at 523. In secondary science, Ireland maintained its 10th position internationally. Earth science is an area of strength, while students perform less well in chemistry and physics. However, minister for education Norma Foley highlighted a need for improvement in some areas, such as stretching the performance of higher-achieving students. The findings suggest that top students are underperforming relative to their peers in countries with similar overall performance.

Another interesting finding in England (and not seen in Ireland) was that more girls than boys were not confident in their mathematical or scientific ability, and reported that they did not like maths or science. However, this was not reflected in the results as girls performed similarly to boys.

What does this all mean?

‘While results for older students have remained stable in Ireland, it has been disappointing to see a significant decline in achievement in England in year 9, in both the short and longer term,’ comments Hannah Russell, chief executive officer of the Association for Science Education (ASE).

‘For students to learn well in science, they need teachers who are passionate and have time and energy to devote to teaching science’

She notes that both maths and science teachers in England said they would like more training in incorporating technology into teaching, and including problem-solving and critical thinking in lessons. To prevent further relative declines in the performance of pupils in England, Hannah argues that the government should invest more in subject-specific CPD. ‘It is clear that access to high-quality continuing professional development for teachers, alongside strong school leadership, are key determinants of success. Given the massive disruption posed by Covid-19, we anticipate that the impact of these factors will increase further over the next four years,’ she adds.

Michael Reiss, professor of science education at the UCL Institute of Education, says that, by TIMSS standards, the drop in science performance in England is large. The suggestions in the UCL/DfE report for the reasons behind the drop ‘are both sensible,’ he continues. ‘Ofqual has been hesitant about too widespread an introduction of three-year GCSEs where this is done simply in an attempt to maximise GCSE outcomes. And while many in science education initially welcomed the end of formal KS2 science tests, the unintended consequence has been a decrease in the time spent teaching science in most primary schools.’ But another issue, he suggests, is that many secondary science teachers (even pre-Covid) have become weighed down by teaching. ‘If students are to learn well in science, they need teachers who are passionate about teaching science, and have the time and energy to devote to teaching science.’

‘Some of the chemistry content in the English National Curriculum is “not fit for purpose”’

‘We shouldn’t be hanging our heads,’ says John Holman, emeritus professor of chemistry at the University of York. ‘We performed well above the mid-point, and the countries above us are very high performing countries.’ However, he acknowledges that the drop in science performance is significant and concerning. ‘It may be because teaching in years 7 and 8 is less thorough because of the start of GCSEs in year 9. Teachers don’t have time to develop concepts, encourage reflection and do experiments.’ But he believes no conclusions can be drawn from the chemistry results. ‘Overall science performance is much more important at this age.’

Should we be comparing?

How valuable are international comparisons anyway? Keith Taber, emeritus professor of science education at the University of Cambridge, says they are only meaningful if the assessment items align equally well with the curriculum in each country being compared. ‘This is very unlikely to be the case here. Otherwise, the scores reflect teaching and learning to different extents, and any comparison is pointless.’ Some countries align curriculum and teaching to focus on the indicators that score well on such league tables, he adds.

Keith would also not read too much into the specific relative performance in chemistry. But he does point out that some of the chemistry content in the English National Curriculum is ‘not fit for purpose’, which might have something to do with it. ‘It contains errors, confusions and inconsistencies that make it difficult for teachers to teach in a coherent way across key stages and still be close to the treatment in the curriculum document.’

So, while some may not read too much into the specifics, this latest set of TIMSS results has certainly drawn out some points that educators in both England and Ireland may need to consider for the future.

No comments yet