Why targeted CPD, at any stage of your career, will improve your confidence in the classroom and your learners’ outcomes

Training to teach is tough. Simultaneously learning how to manage the classroom dynamic and develop knowledge of a plethora of pedagogic approaches, while keeping students attentive and seated, is enough to test the limits of even the most capable trainee. Something often taken for granted is subject knowledge (SK), as most trainees hold an undergraduate degree in the subject they will teach.

It’s nearly 20 years since an RSC policy bulletin stated that: ‘The best teachers are those who have specialist subject knowledge and a real passion and enthusiasm for the subject they teach … the Royal Society of Chemistry believes that young people deserve to be taught the sciences by subject specialists.’

However, numerous studies have shown that pre-service teachers with good honours degrees in their subject hold misconceptions and have curriculum knowledge gaps. And due to the shortage of teachers in the profession, the growing number of non-specialists teaching chemistry means that a focus on SK is more important than ever.

What makes a good teacher?

I was involved in a research project at the University of Southampton, inspired by the question: what makes a good chemistry teacher? We interviewed 11 teachers and then developed a survey, which 51 teachers from across the UK completed.

The most likely explanation for this is that participants struggled with the topic in their own studies

A key aspect the survey explored was their confidence in teaching different areas of the A-level specification. The interviews showed a clear correlation between lack of confidence in a specific topic and the teachers’ perceived level of SK linked to that topic.

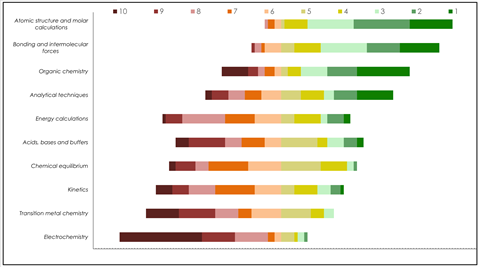

A key aspect the survey explored was their confidence in teaching different areas of the A-level specification. The interviews showed a clear correlation between lack of confidence in a specific topic and the teachers’ perceived level of SK linked to that topic (see chart).

Self-reported confidence in a particular topic does not necessarily correspond with a solid grasp of SK, but the interviews provided evidence that there is a relationship between the two. The most striking feature of the data was the widespread lack of confidence in teaching electrochemistry. The most likely explanation for this is that participants struggled with the topic in their own studies at A-level and undergraduate level.

The following teacher response sheds light on the reasons for a lack of confidence in electrochemistry: ‘There is so much confusion … yes or no, true or false, plus or minus, reduction or oxidation … because, unless you’re precise, if you’re talking to [students] about even what a reducing agent is, you say “itself is oxidised”. They can just make a mistake. It’s too easy for them to kid themselves that, like an electrode potential, they get Ecell to be -2.3 and it’s +2.3, and they go “Oh no, I see where I’ve gone wrong, I meant to do that”, but they don’t understand.’

How to break the cycle

One teacher suggested that the problem is cyclical, as students find electrochemistry challenging, then some of them then go on to be teachers – with their own students subsequently failing to develop a strong understanding of the topic. Survey participants expressed a general lack of confidence in physical chemistry topics, along with transition metal chemistry, where they cited needing to rote learn facts as being a major issue.

When a teacher’s understanding is poor, this can lead to under-developed pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) and, as a result, they disseminate misconceptions to their students. However, it’s not straightforward to fix the problem. Initial teacher education or training programmes are packed enough, and trainee teachers are already overburdened with workload.

It could be argued that SK in 11–14 and 14–16 chemistry is more important for trainees, who may not get the chance to teach at post-16. With this in mind, it might be better to find ways to support newly qualified and early career teachers with SK development. However, some of the teachers participating in our study had many years of experience and they could also benefit from it. It would be straightforward to create online resources that convey the raw SK and lead teachers through worked examples, although face-to-face masterclasses would be preferable if practicable, perhaps with ongoing coaching to support PCK development.

The value of subject-specific CPD has been extolled by the RSC, the Chartered College of Teaching and the Institute of Physics (IOP), among others. The IOP suggests presenting new ideas and practices with research evidence. They also propose ensuring teachers have the chance to reflect on and challenge their existing beliefs and theories, which may help get rid of deep-seated misconceptions and build confidence. Resources should be high quality and genuinely meet the needs of the audience. Of course, funding for such interventions is a key sticking point at a time when budgets are already stretched, but any initiative that ultimately enhances outcomes for students is surely worth the money.

Boost your PD

Why not get started with some targeted CPD to improve your practice right now? Explore all that the RSC has to offer to bolster your SK and PCK …

David Read is a principal teaching fellow in chemistry at the University of Southampton

No comments yet