Organic chemistry doesn’t have to be difficult – try these confidence-boosting, practical tips with your students

Organic chemistry has a reputation as being difficult for students. There are lots of reasons for this: it requires confidence in all the domains of Johnstone’s triangle, it has an extensive new vocabulary, and there are no algorithmic shortcuts to success. Another source of difficulty is a mismatch between the expert and novice view. To teachers, organic chemistry seems easy. I have often heard teachers say that students ‘just have to learn it’, which dismisses the learner’s experience and oversimplifies the issue. Try these strategies to boost your students’ confidence when tackling organic chemistry topics such as alcohols, carboxylic acids and esters.

1. Work with multiple representations

Organic chemistry has a language of its own from the names of the molecules and their reactions, to new terms like ‘functional group’. Time should be spent on gaining some fluency with this new language, as not recognising the focus of a question is a big barrier to success in this topic.

Students needs to be able to recognise alcohols, carboxylic acids and esters in multiple representations, including names, structural formulas, diagrams and even models. Matching exercises or multiple choice questions promoting thinking about different representations are good activities for starting a lesson. They have a low threat level as they operate in the recognition domain of memory and can be motivating for students.

2. Connect with prior knowledge and emphasise similarities

By the time students reach this topic they already know a lot of chemistry, especially about acids. Connect the new learning with their secure prior learning. Carboxylic acids do exactly the same reactions as the acids that students are more familiar with – so it’s worth emphasising that this is only a small extension of their knowledge. Those patterns of acid reactions that they already know (such as acid + alkali → salt + water) apply to carboxylic acids as well.

3. Look at how to write equations

Do not use molecular formulas when writing equations in organic chemistry. Can you hear me shouting that from the page? It’s the feedback I give most in this topic. This issue is a symptom of isomerism not being a feature of the 14–16 chemistry curriculum.

For example, I will commonly see the equation for the complete combustion of ethanol written as: C2H6O + 3O2 → 2CO2 + 3H2O. This, of course, could also be the equation for the complete combustion of methyl ether, but that is beyond the scope of the course. Despite this, students will lose marks for using molecular formulas that obscure the meaning of the equation – so be prepared to really emphasise this in class.

Writing salt formation equations

A. Salt formula written conventionally with metal first:

2CH3COOH + Na→ 2NaOOCCH3 + H2

2CH3COOH + Mg→ Mg(CH3 COO)2 + H2

B. More intuitive arrangement of species, highlighting attraction between the positive metal ion and the negative ethanoate ion:

2CH3COOH + Na→ 2CH3COONa + H2

2CH3COOH + Mg→ (CH3COO)2Mg + H2

Equations of reactions of carboxylic acids are also tricky. Students need to know which H is the acidic one so they can apply this to the acid equations familiar to them. Colour coding, bolding or underlining can scaffold this for them. Also consider how you set up equations for salt formation to ensure the barrier to understanding isn’t too high. Students will be used to writing the formula of a salt with the metal part first, but this can obscure the meaning with organic salts. In the reactions of ethanoic acid with metals shown above, the conventionally written salts make it difficult to understand that the H+ has been lost and an O- left on the ethanoate. The second arrangement is much more intuitive.

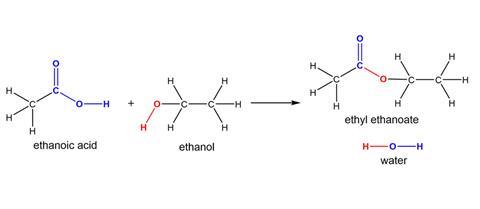

4. Highlight functional groups to aid understanding

The molecular formula C3H6O2 could be an ester or an acid. The most important part of these organic molecules is their functional group. Functional groups are the reactive parts of the molecules – the bits that change when chemical reactions occur. This needs lots of emphasis. When drawing an alcohol, it matters that the carbon chain is joined to an O which is then joined to a H (never mind the horror show of valencies that results if it’s drawn the other way).

Colour is a great way to add emphasis and draw attention to functional groups. It’s especially useful in allowing students to track where atoms end up in reactions. So much so, it’s used in the most popular organic chemistry books at undergraduate level as well.

1 Reader's comment