Simon Lancaster focuses on gender bias in students' module evaluations

![Sunny scotland 300tb[1]](https://d1ymz67w5raq8g.cloudfront.net/Pictures/480xAny/6/2/6/113626_sunnyscotland_300tb1.jpg)

In my last post I focused upon the metrics of student evaluations: the absurdity of averaging Likert scales and the lack of actionable insights. If only those were the limits of the faults of evaluation by questionnaire.

Perhaps you recall the example of Prof MyMate, the fictional colleague who so polarised their students? Paul, who edits these ramblings into coherent articles, wanted me to assign a specific gender to Prof MyMate. I vetoed his suggestion.

I did so because MyMate’s gender matters. A professor’s gender quite literally makes a difference to how they are evaluated.

Evaluations, it turns out, are subject to all sorts of biases.

All your bias

Let’s start where we left off in the previous article, with me bemoaning the lack of actionable insight from the surveys my students were completing. Perhaps I was a little harsh. The students gave me positive scores, the qualitative comments were very encouraging. As for the odd gripe … well they probably hadn’t even attended the majority of my teaching.

Confirmation bias is the all-too-human tendency to select, interpret and preferentially recall information to support our already-held beliefs. Evaluations that lack incision are prime targets for an educator’s confirmation bias.

Every lecturer on our courses is evaluated against four ostensibly different categories: knowledge; enthusiasm; response to student needs; organisation and presentation. Why then is there rarely a significant difference between those four indicators? Might it be that students are actually measuring something else?

Pellizzari and coworkers have presented evidence [M. Braga et al, Econ. Educ. Rev., 2014, 41, 71–88] that students evaluate their lecturers on the basis of something they call their ‘realised utility’, which is apparently economist-speak for how much they enjoyed the course. They report a negative correlation between evaluation scores and the effectiveness of the teacher measured in terms of examination results.

The implication is that students are not good at evaluating the quality of their teaching. I would like to believe that enjoyable teaching doesn’t mean poor teaching, but I do believe that student enjoyment alone cannot be assumed to mean teaching is effective.

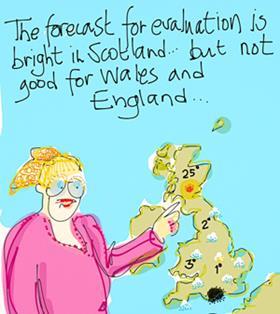

The principle of ‘realised utility’ has fascinating and wide-reaching implications beyond teaching style. Pellizzaris’ group have found evidence for a relationship between evaluation result and the weather. I think we all intuitively know what kind of day on which to choose to conduct our evaluation.

An unfair system

If the bias towards positively evaluating lecturers whose course you enjoy is understandable but misled, what are we to make of the systemic bias against female academics in student evaluations?

The move to online education has provided opportunities to anonymise instructors when collecting evaluation data. In one study a male and female academic posed (online) as their own gender to one class and the opposite gender to the second class. Against every evaluation category the academic perceived as male scored more highly, even when the category was as innocuous as promptness. An observation every promotion committee should probably be aware of.

To recap, the module evaluation is subjected to methodological abuse, rarely produces actionable insights beyond appealing to our confirmation bias, is as fickle as the weather and can exhibit shocking and groundless inequality.

But I’m alright, I always do well in module evaluations.

I sincerely hope that no student reading this takes offense. I am criticising the system not students. Students are simply exhibiting the same behaviour any group of human beings would do given the same circumstances. Try to be aware of the pitfalls when completing the surveys and aim to back every tick or circle on a Likert scale with a supporting statement. The lecturers are listening!

Simon Lancaster is a professor of chemical education at the University of East Anglia, UK

Images © Simon Rae

No comments yet