Use these 5 teacher-tested ideas to help students get on top of this challenging topic and perform better in exams

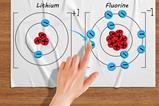

The topic of structure and bonding is known to be a bit of a challenge. It underpins so much of the other chemistry that students encounter and, to us, as expert teachers, it can seem relatively simple. However, to 14–16 students it is very abstract, making use of models which themselves rely on understanding of atomic structure. It’s also difficult to find classroom activities that are engaging and add variety to lessons. This makes it a difficult topic where we often find ourselves correcting students making incorrect statements long into their post-16 education.

Here are five ways to teach this tricky topic and boost your students’ understanding.

1. Consider the context

There is no perfect sequence for teaching the three different ‘types’ of bonding structures covered in the 14–16 age range. It very much depends on when you introduce atomic structure and how secure students are with the core concepts of that topic. Beware of just taking an off-the-peg resource or following a syllabus sequence before considering it in the context of your cohort. This is definitely a discussion to have as a department, taking into account student experiences and different levels of prior achievement, as well as the skills and experience of your teaching staff.

-

Structure strips to support this topic

These scaffolded writing activities offer prompts to help learners develop and consolidate their understanding. Discover structure strips for Allotropes of carbon, Covalent bonding, Ionic bonding and Metallic bonding in our collection.

2. Make the abstract more concrete

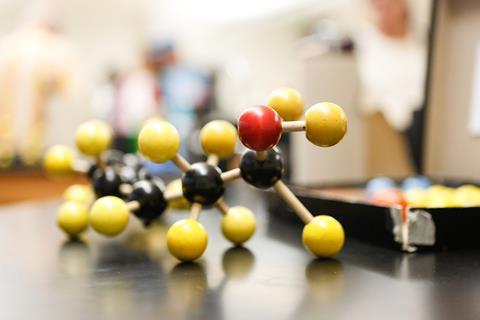

Physical models help secure students’ knowledge far better than textbooks or PowerPoint diagrams. There are lots of commercial models available, for example Molymod structures of the bonding in a diamond, but these can be expensive if your school doesn’t already have them.

My mantra is always: fewer, better words

Thankfully, informal models from craft materials can be just as powerful. For example, we have a very old set of models of giant ionic structures made of painted wooden spheres which show the lattice packing very clearly. Have a dig around in your school’s store cupboards and ask colleagues, especially technicians, to find what’s available. Plan how you will use the models in class and how you want students to interact with them.

3. Model thinking with decision trees

Ask yourself what processes you go through to decide what category of bonding an element or compound belongs to. Often students struggle to construct this kind of internal narrative. Distil it into decision trees or dichotomous key style diagrams to make the thinking much more obvious, and even improve exam success. Construct these diagrams with students and then provide them as a resource to support them in writing answers to questions – this is particularly helpful for lower achievers. As students gain confidence, remove the support so they can internalise the thinking.

4. Refine, refine, refine

Learners commonly use far more words than they need when tackling questions on structure and bonding. Remind them that the exam board tend to be very generous in their allowance of lines for written answers, and they don’t have to fill them all. It takes time and practice to help students write efficiently. Take their waffly answers and edit them to refine each one to the best it can be. My mantra is always: fewer, better words. Blanking out the unnecessary words with a black marker can be a really striking way of showing students where they’re wasting time and potentially robbing themselves of marks. Students really enjoy taking a black marker to each other’s (photocopied!) work.

5. Focus on assessment as exams approach

The structure and bonding content at 14–16 hasn’t changed in many years, but exam boards can be quite picky with mark schemes. I really dislike focusing purely on assessment when exploring chemistry, but it is a necessary evil as exams get nearer.

The emphasis and marks for bonding questions vary slightly for different exam boards and have changed over time. For this reason, you might find that past paper answers to the questions you use in class are subtly different to the ones your students will be marked on in their final exams. This is particularly true if you pull exam questions from a database that includes several years of assessments. For example, a few years ago, my colleague had a top strategy for getting all the marks in an answer explaining the high melting point of an ionic compound. He used to teach the students the acronym SEABOCI – strong electrostatic attraction between oppositely charged ions – which would get them three marks. But, more recently, examiners require students to state that the attraction acts in all directions in a giant lattice, and mention energy. So, in revision close to the exams, focus on the most recent mark schemes.

Kristy Turner

2 readers' comments