The emergence of new techniques and pigments within Greek art

Introduction

In the 5th century BCE Greece was in a time of change. The art was evolving to reflect the changes that were taking place in the thinking or philosophy of the day.

The techniques of Greek painting and expressions of image advanced from a flat non-emotional representation to an expressive frontal form. Depth and perspective was important. Realism as an expression of beauty was now the goal of the Greek artist.

The methods of representation included such techniques as three-dimensional perspective, the use of light and shade to render form, and three-dimensional or trompe l’oeil realism (the use of perspective to create an illusion of three-dimensionality).

As the Greeks developed their materials and techniques, so styles changed and offered a means of dating the art. Sadly very little of the painted art remains, maybe because the main medium for the painting; whitened wooden panels (pinakes) was prone to rotting and destruction. Hence the main evidence is from the paintings on stone.

Most artists and architects were male artisans earning little money but working in family businesses so that skills were handed on from father to son. It was not until the Hellenistic Period that artists began to earn more through royal patronage and, as a result, travelled distances to execute work.

Early periods of Greek art

Pottery

The Geometric period (900-700 BCE) had seen the development of pottery painted with designs based upon geometric shapes such as triangles, dots, straight and angled lines. By 700 BCE silhouettes of humans were appearing in the paintings on pots, especially those being used as burial monuments. Initially the silhouettes were angular; later they were more natural, rounded forms.

During the Orientalising period (700-600 BCE) the art was influenced by that from Egypt and other Near East civilisations. The geometric design was replaced by bold colourful figures such as owls and lions, along with rosettes and other intricate designs.

The Archaic period (600-480 BCE) combined the eastern styles with the old geometric designs, and the depiction of human and animal figures reached new heights with scenes from mythology and, later, everyday life.

During the Archaic Period two different techniques were used for vase painting. The earliest, called black-figure painting was invented in Corinth in the 600’s BCE. In this style the figures were painted on to the vase with liquid clay. When fired in a special kiln the clay figures turned a glossy black. The black silhouettes were incised or scratched to reveal the red body of the vase giving the figure detailed structure. These detailed structures were emphasised by outlining with white or red paint.

Then, in about 530 BCE, a new technique was developed in which the red/black colour arrangement was reversed; backgrounds were painted black and more natural, lifelike figures left in the red colour of the clay. These figures had details added using black paint. On some rarer vases the whole background was painted an ivory white, which made the figures more prominent.

Architecture

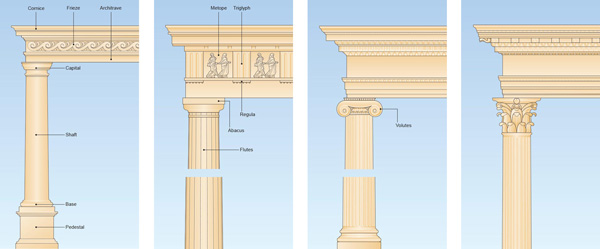

It was in the Archaic Period that the Greeks began to build temples to their gods. They consisted of a small, freestanding structure called a cella surrounded by a row of columns (a colonnade). Inside the cella was a statue of the god to whom the particular temple was dedicated. Three styles, or ‘orders’, of design were adopted: Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian. Each order is identified by the distinctive design of its columns and capitals see Figure 1.

- The Doric order; a simple, sturdy, and relatively undecorated design with no base - was developed by the Dorian tribes on the Greek mainland.

- The Ionic order; a delicate and ornate style with longer more slender columns often topped with a spiral or scroll-shaped capital - was developed by the Ionian Greeks living along the coast of Turkey.

- The Corinthian order; a variation of the Ionic with capitals carved as acanthus leaves instead of scrolls - was developed in the city of Corinth during the classical period, well after the Doric and Ionic styles.

Figure 1: Parts of a Column and examples of general, Doric, Ionic and Corinthian orders.

Peter Bull

Paint was used to enhance the visual appearance of the architecture. Certain parts of Greek temples were painted from the Archaic Period. This painting was frequently polychromic (many colours) in the form of bright colours applied directly to the stone. Work at the British Museum has revealed evidence on the Parthenon marbles of the use of Egyptian Blue, and there are Archaic Period examples at Olympia and Delphi.

Sculpture

Developments in sculpture were rapid during the Archaic Period, particularly in the portrayal of the human figure.

At the beginning of the period sculptors began to carve large life-sized figures of men and women. These early figures had stiff and upright postures, with males typically portrayed nude and known as a kouros, and females clothed in elaborately draped garments and known as a kore. The arms of the statue were close to their sides and one leg was extended slightly forward similar to that seen in Egyptian sculpture. Many of these sculptures were used in temple sanctuaries and as grave monuments.

Many were made from local marble as in Naxos, Samos and Paros. Where there was no local marble, the statues were carved from limestone. By the late 6th century BCE some were being cast in bronze with features being picked out in copper and silver and eyes inlaid from glass or stone. As in other ancient cultures there can be no doubt there was a tradition of sculpture in wood about which we know very little because wood decomposes easily.

By the end of the period, sculpture had become much more realistic. Poses were less stiff and more natural. The drapery on female figures better reflected the shape of the underlying body. Figures were also more idealised. This means they were meant to depict the ideal male or female form.

Like all Greek sculpture, the statues were painted in strong and bright colours. The paint was frequently limited to parts such as clothing and hair, with the skin left in the natural colour of the stone, but the paint could also be used to cover sculptures in their totality. The painting of Greek sculpture is not merely an enhancement of their sculpted form, but characteristic of a distinct style of art.

Later periods of Greek art

Architecture

The Parthenon was built between 447 and 432 BCE, during the Classical Period (480-323 BCE). It is considered the greatest example of the Doric order, larger than the standard temple and measuring 70 metres long by 31 metres wide. The colonnade has eight columns across the front and across the back, and each side is composed of 17 columns. Built entirely of marble it was decorated with sculptures portraying various battles, a procession of Athenians honouring the Greek goddess Athena, and scenes from Athena’s life.

Another notable Doric temple of the Classical Period is the temple of Apollo at Bassae. Built between 420 and 400 BCE, it contains the earliest known Corinthian columns. After 400 BCE architects continued to work with the Doric and Ionic orders, adding ornamentation and experimenting further with combining the orders in a single building.

Among other architectural forms created by the Greeks during the Classical period were the stoa, used to enclose spaces and the theatre. The stoa was a long roofed hall or promenade with a solid back wall and a colonnade at the front. It was used as a market, a law court and a shelter from the weather. Theatres were an important part of every Greek city, usually situated against a hill where the audience could sit to watch the performances. Performances were dedicated to Dionysus, the god of wine.

Sculpture

Few original sculptures of the classical period survive. Most of what is known about the great sculptors of this age comes from copies made by the Romans. There was a growing interest in realism and the idealisation of the human body. This can be witnessed in the life-sized bronze sculpture known as The Charioteer (circa 470 BCE). Bronze (an alloy of copper, tin, and sometimes arsenic) was a favourite material from which to make statues in the Classical Period. Sadly many were melted down long ago to make such things as spearheads.

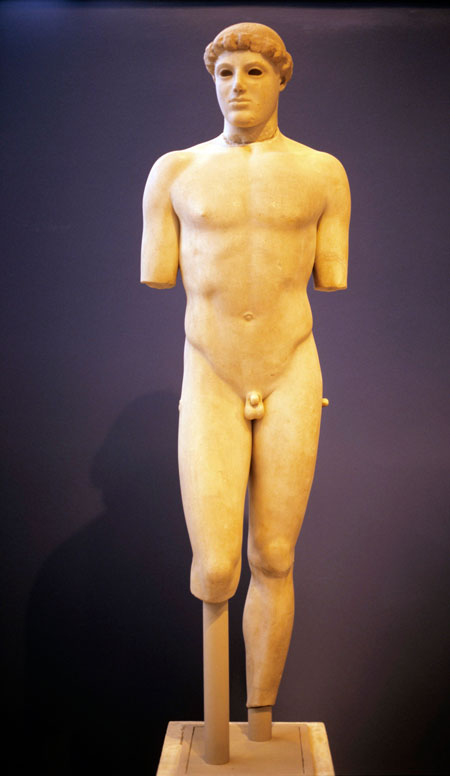

After 450 BCE the style of sculpture reached a climax of skill and the first sculpture to illustrate this level is thought to be The Kritios Boy (480 BCE) by Krito. It depicted the human form in a realistic manner, being sculptured to accurately reflect human proportions see Figure 2. The muscles covered by taut skin are clearly defined.

Architecture

The Parthenon was built between 447 and 432 BCE, during the Classical Period (480-323 BCE). It is considered the greatest example of the Doric order, larger than the standard temple and measuring 70 metres long by 31 metres wide. The colonnade has eight columns across the front and across the back, and each side is composed of 17 columns. Built entirely of marble it was decorated with sculptures portraying various battles, a procession of Athenians honouring the Greek goddess Athena, and scenes from Athena’s life.

Another notable Doric temple of the Classical Period is the temple of Apollo at Bassae. Built between 420 and 400 BCE, it contains the earliest known Corinthian columns. After 400 BCE architects continued to work with the Doric and Ionic orders, adding ornamentation and experimenting further with combining the orders in a single building.

Among other architectural forms created by the Greeks during the Classical period were the stoa, used to enclose spaces and the theatre. The stoa was a long roofed hall or promenade with a solid back wall and a colonnade at the front. It was used as a market, a law court and a shelter from the weather. Theatres were an important part of every Greek city, usually situated against a hill where the audience could sit to watch the performances. Performances were dedicated to Dionysus, the god of wine.

Sculpture

Few original sculptures of the classical period survive. Most of what is known about the great sculptors of this age comes from copies made by the Romans. There was a growing interest in realism and the idealisation of the human body. This can be witnessed in the life-sized bronze sculpture known as The Charioteer (circa 470 BCE). Bronze (an alloy of copper, tin, and sometimes arsenic) was a favourite material from which to make statues in the Classical Period. Sadly many were melted down long ago to make such things as spearheads.

After 450 BCE the style of sculpture reached a climax of skill and the first sculpture to illustrate this level is thought to be The Kritios Boy (480 BCE) by Krito. It depicted the human form in a realistic manner, being sculptured to accurately reflect human proportions see Figure 2. The muscles covered by taut skin are clearly defined.

Figure 3: The Vatican Apoxyomenos by Lysippus.

© NICK FIELDING / Alamy

It was between 400 and 323 BCE that the influence of Athens on Greek art declined. Differing styles emerged with different ideas. Praxiteles introduced a soft, subtle style. In contrast Scopas conveyed strong emotions by his use of twisting, active poses.

Relief sculpture, carved to stand out from a flat background and often decorating the temples as friezes, would run above columns and feature human and animal figures. An example is the frieze that runs along the outer top of the Parthenon’s cella.

The most respected form of art, according to authors like Pliny or Pausanias, were individual, mobile paintings on wooden boards, technically described as panel paintings. The techniques used were encaustic (wax) painting and tempera. Such paintings normally depicted figural scenes, including portraits and still-life; we have descriptions of many compositions. Realism was highly valued and well developed.

Due to limited local minerals, Greek artists worked with an extremely small palette. Pliny claimed “four colours only were used by the illustrious painters to execute their immortal works”. These pigments are known as the ‘four earth tones’ or tetrachromy in Greek see Figure 4. Namely: Red Ochre, Yellow Ochre, Chalk White (Gypsum White) and Vine Black (Charcoal Black). Apelles (c370-c320 BCE) has been acknowledged as the principal advocate of the ancient tetrachrome palette as seen below. From this palette a wide range of colours could be mixed, including all flesh-tints from pale to swarthy.

Figure 4: The Tetrachrome palette.

Don Pavey, Colour and Humanism (2003)

It is worth noting the absence of blue, green, and purple. Despite this the four-colour palette was influential on the Venetian painters and even revived by the Cubist painters early in the 20th century. Yet it is clear that the Greeks did paint with a wider palette than four colours and what we see here is a difference between the theories of the philosophers and the practice of the artisans.

Artisan painters mixed or blended pigments to create different hues but the philosophers despised this mixing preferring to write of the four primary colours. Later reliance on the four-colour palette might not therefore reflect actual practice.

The Tetrachrome palette and other coloured pigments used by the artists had to be sourced from minerals around Greece or imported from islands close by. Much of the Greek knowledge about pigments had come from the Egyptians.

In order to produce a brownish red or a red earth hue the Egyptians and the Greeks partially burnt ivory or found haematite (iron oxide) or red ochre. Burning the dregs of wine or importing Egyptian Blue produced the deep blue colours. Black could be made from burning ivory and dry dregs of wine to produce carbon and the product could also be used as a varnish. Hydrated red ochre (iron oxide) produced yellow ochre and gypsum (calcium sulfate) or chalk (calcium carbonate) was used for whites. The beauty of these earth tones is they work in relation to each other to create a harmonious and subtle vibrancy to figure and could be mixed to create a range of hues.

Many wall paintings appear to have been produced in the Classical and Hellenistic periods but, due to the lack of architecture surviving intact, not many are preserved. The most notable examples are the elaborate frescoes from the 4th century BCE “Grave of Phillipp” and the “Tomb of Persephone” at Vergina in Macedonia. Greek wall painting tradition is also reflected in contemporary grave decorations in the Greek colonies in Italy, e.g the famous Tomb of the Diver at Paestum. This would indicate the spread of the art styles across the Greek world.

Some scholars suggest that the celebrated Roman frescoes at sites like Pompeii are the direct descendants of Greek tradition, and that some of them copy famous panel paintings.

Alongside Apelles a number of Greek painters were written about by the Romans and as result accounts of their work have been passed down to us. Among these were Agatharcus (c440-410 BCE) from Samos who wrote a treatise on scene painting that inspired Anaxagoras (c500-428 BCE) and Democritus (c460 BCE) to work out the rules of perspective. Euphranor (c360-330 BCE) worked in Athens and wrote much on colour and symmetry. Nicias (4th century BCE) experimented with shading to create three-dimensional impressions. Literary works of the time note not just names of individual painters but their use of realism, colour, shading and perspective (the technique of showing the illusion of distance on the flat surface of a painting).

Mosaics and cement

As early as 500 BCE the Greeks began creating mosaics; pictures formed by laying small coloured stones, pieces of marble, or glass in cement. In early mosaics black and white river pebbles were set into a cement floor to create pictures of animals, flowers, or scenes from mythology. These mosaics served as decorative floor coverings in important rooms of a house.

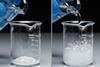

Cement is not a new substance. The Egyptians used calcined gypsum (gypsum (calcium sulfate) partially dehydrated by heat) as a cement. The Greeks and Romans on the other hand used lime cement, made by heating limestone and adding sand to make mortar, with coarser stones or aggregate to make concrete.

When heated, limestone (calcium carbonate) forms lime (calcium oxide). When lime is mixed with water it slowly turns into the mineral portlandite (calcium hydroxide) in the reaction:

CaO + H2O —> Ca(OH)2

If the lime is mixed with excess water then the lime is slaked and is fluid. Over time it hardens. Mixed with sand to form mortar it can be packed between stones and bricks to bind them. If mixed with fine sand and spread over the surface of a wall it is plaster. Exposed to the air the slaked lime reacts with carbon dioxide to form calcite (calcium carbonate) and hardens. The Greeks used these substances to form a plaster surface for painting on and the cement for creating mosaics.

From around 1000 BCE the Ancient Greeks found that mixing lime with fine volcanic ash, which contains silicon, and then slaking this formed a new substance; calcium silicate hydrate (SiCa2O4.xH2O) often known as C-S-H. This material is an amorphous gel with no crystalline structure but it hardens quickly, even in water, and is more durable. Although the Greeks came up with the mixture the Romans developed its use by adding aggregate and now Roman concrete is found all over the Roman buildings from the Roman Empire.

The Hellenistic period

The period between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE and Rome’s conquest of Greece in 146 BCE is known as the Hellenistic period. During this time Greek culture continued to influence the many non-Greek people conquered by Alexander throughout the Middle East, spreading Greek culture and ideas across the civilised world. The Roman Empire later spread Greece’s influence throughout most of Europe and into northern Africa.

Architects working in many parts of the Greek world continued to use all three orders, particularly the Corinthian, and this style was developed by the Romans into a similar design and used throughout the Roman Empire. Yet architects also began to combine different styles and change the proportions of elements in buildings. With the invention of the stone arch it offered new possibilities of construction and the rise of great cities.

Hellenistic sculpture was still used for dedications and grave monuments but was also used as decoration and propaganda (created to persuade others).

The earlier classical styles were still influential and Hellenistic sculpture portrayed youthful adults in peak physical form, children and the very old. Two of the most famous sculptures of ancient Greece date from this period. The first is the marble sculpture known as Venus de Milo, or Aphrodite of Melos, carved by an unknown artist and missing its arms but still an outstanding expression of the human form. The second is Winged Victory of Samothrace also by an unknown artist and depicting the Greek goddess Nike see Figure 5.

Figure 5: Winged Victory of Samothrace Nike.

© The Art Archive / Alamy

Some original Greek paintings from the Hellenistic period have survived to modern times. They are mainly found in the tombs of Macedonians (people from Macedon, a region in northern Greece). The complicated composition, use of colours and perspective indicate that wall paintings of this time were of high quality.

The stone walls were carefully prepared by recessing the stone to contain the painting. The surface was smoothed and painted with white lead carbonate to form a flat, brilliant white, ground surface. Next the artist incised the design in the ground layer this was then marked out using black charcoal. To create the final painting the artist used overlapping layers of pigment to create colour and tones.

As in other times the artists used both local and imported minerals, synthetic inorganic pigments, and organic dye stuffs precipitated on white clay. The binder is difficult to determine but there is some evidence that a wax was used by some artists.

Methods of making mosaics also improved and instead of using different coloured pebbles, they moved on to use small cubes of cut stone or glass. Being cut they allowed the artist to lay the small bits closer to each other and in more intricate patterns. They were more colourful and complex.

Downloads

The emergence of new techniques and pigments

PDF, Size 0.31 mbStyles and Techniques, new Pigment

PDF, Size 0.18 mb