Introduction

Under the influence of the Ancient Greek views of art, artists of the Renaissance saw the key to truth and beauty in the past. Renaissance artists studied the sculptures and monuments of Greece and Rome and emulated them in their own work, ie they imitated the art. This perspective of art has echoed down the centuries to influence the appearance of Western art and architecture today.

But were the Renaissance and later artists under an illusion? If those artists had looked more closely they might have found something that would have changed their vision of art and had a profound effect on their own practice.

The appearance of the Ancient Greek art has entrenched a view that still is difficult to accommodate. It is none other than the association between Classical art and the look of white, unblemished marble.

Can you imagine the Athenian acropolis as a painted colourful stone building? It does seem somewhat blasphemous in terms of our view of Greek art.

Polychromy: painting on statuary and architecture

The clean white surface of Michelangelo’s ‘David’ (see Figure 1) or Bernini’s ‘St. Teresa in Ecstasy’ would have been considered unfinished by an Ancient Greek artist.

Figure 1: Bernini’s ‘St. Teresa in Ecstasy’ (1647-52).

© VPC Photo / Alamy

Much of the statues and architectural sculpture of ancient Greece was colourfully painted in a way that is described as polychrome (from Greek many and colour). However, due to intensive weathering and other effects on the stone, the polychromy on Ancient Greek sculpture and architecture has substantially or totally faded.

What this means is that the sculpture and architecture of the ancient world was, in fact, brightly and elaborately painted. The only reason it appears white is that centuries of weathering have worn off most of the paint.

The accepted view

Let’s go back a stage and look at how many of these sculptures came to our museums. People digging in the ground or swimming in the seas have been finding artefacts, some of which have been sculptures. The consistent trend is they have always been without colour. By the 19th century this ‘finding’ had become systematic excavation of specific sites and still the persistent trend was for sculptures with no colour.

This lack of colour enforced a particular view amongst art historians: Ancient Greek art was without colour. So strong was this idea that influential art historians, such as Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717-1768) founder of modern archaeology and father of art history as a discipline, strongly opposed the idea of painted Greek sculpture and dismissed proponents of painted statues as eccentrics. Due to this the accepted view became that Ancient Greek sculptures were white marble or bonze coloured bronze.

Evidence for polychromy

It is not actually true that all sculptures were found totally devoid of colour. Some were found with small elements of colour still adhering to the surface. This supports the view that in antiquity statues were painted.

Over time some pigments applied by the artists have faded due to burial conditions, aging, and overzealous cleaning. Where found the evidence indicates that sculpture was originally polychrome. Ancient wall paintings and vessels depict vividly coloured statues, and Greek and Latin texts refer to the art of painting figures.

The question is, ‘How accurate is the practice of looking for this colour on the statues?’ Today, using laboratory techniques, archaeologists and scientists are able to identify traces of ancient polychromy and present hypothetical reconstructions of the statues.

Preservation of colour

First conservers have to determine the preservation of the colour and then consider the composition of the pigments. Preservation of traces of original colour on an ancient stone sculpture may be either direct or indirect.

In some cases remains of colours are directly preserved i.e. they are still there as colour on the surface of the statue.

In other cases the pigment is worn away due to exposure to weathering. This creates differences in tone of colour of the stone. Aging can make the painted surface darker and revealed stone lighter. This produces what is known as ‘colour shadows’ revealing where paint could have been applied, and is called indirect preservation.

Pigment durability will also produce differences in the tone of colour of the stone. A resistant pigment will protect the stone while a less resistant one will wear down. This leads to a ‘weathering relief’ showing us where paint might have been applied.

Even during the execution of the art actions of the artist can help preserve the pigments. An artist will often incise (cut) a design or shape into the stone to act as a guide. They will sometimes pick this out with a colour

Examination of the sculpture using the naked eye, lens or microscope will reveal pigments remaining on the sculpture. Also, using photography in visible, infrared or ultraviolet light can reveal organic materials found with pigments.

Organic materials such as oils or egg were used as binders in paints and others were used as colouring agents. The infrared and ultraviolet light activate chemicals in the organic materials and they fluoresce revealing where paint was originally applied.

Weathering and incised surfaces can be revealed using raking light, i.e. illuminating the surface of objects at an oblique angle or almost parallel to the surface. This provides contoured information on the surface topography and relief of the artefact.

Analysis of pigments

When a pigment is found a small sample is taken and analysed using a range of techniques such as scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with X-ray, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, Raman laser spectroscopy and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry.

The pigments found tend to be, in the main, inorganic, i.e. made from minerals or natural earth colours. There are some organic pigments which have been extracted from plants. Lastly there are two synthetic pigments. The range is as follows:

- Cinnabar, mercuric sulfide (HgS), was a popular, expensive red mineral pigment;

- Ochre, an earth containing iron oxide (Fe2O3), found in hues from orange to reddish brown;

- Minium, red lead, lead tetroxide (Pb2O4), a red pigment;

- Madder lake, or alizarin 1,2-dihydroxy-9,10-anthracenedione, is a pinkish red organic pigment from the root of the madder plant;

- Orpiment and realgar, both arsenic sulfides (orpiment As2S3, realgar AsS) minerals used to produce yellow pigments;

- Azurite is a copper carbonate (Cu3(CO3)2(OH)2) mineral and the source of a deep blue. It is an expensive pigment. It can turn into a greenish hue through weathering to malachite;

- Egyptian blue is the oldest known synthetic pigment, made from calcium, silicon and copper;

- Malachite, a green copper carbonate (Cu2(CO3)(OH)2) mineral closely related to azurite – and just as expensive;

- Bone black and vine black are organic pigments, mainly carbon (C), resulting from carbonisation;

- Lead white, a lead carbonate (2PbCO3·Pb(OH)2), is a synthetically produced white pigment.

Case study: Trojan archer from temple of Aphaia, Aegina

More recently archaeologists in Germany, led by Vinzenz Brinkmann and his wife Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann, and others in England at the British Museum, have used powerful scientific methods and found evidence of this colour on some objects that look as if they never had colour.

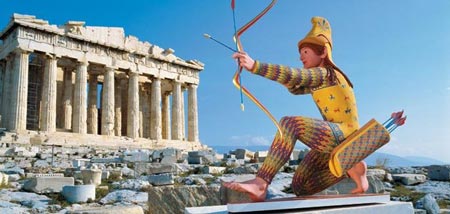

One example is the life-sized figure of a Trojan archer from the temple of Aphaia on the Greek island of Aegina. It was excavated in 1811 and acquired by King Ludwig of Bavaria and is now at the Stiftung Archäologie, Munich.

Using high intensity light and ultraviolet light to look for the evidence of colour on the statues he has spent the last 25 years restoring the colour to copies of ancient statues using pigments that would have been used by the Ancient Greeks such as green from malachite, blue from azurite, yellow from ochre and arsenic compounds, red from cinnabar, and black from burned bone and vine.

When the original is examined under raked light it is possible to see faint incisions of animals such as a cat or griffin.

The surface of the sculpture was once covered in brilliant colours, but time has erased them. Oxidation and dirt obscures or darkens any trace of pigments that remain on the surface, however, using physical techniques such as ultraviolet light and chemical analyses, Brinkmann has established the original colours with a high degree of confidence the ultraviolet light reveals colour shadows even where the naked eye can pick out nothing distinct. To create the replica statue, three-dimensional laser scanning is used with computer imaging.

The archer wears a shirt and leggings covered all over with an intricate design of red, yellow, blue and green diamonds. Over the shirt he wears a bright yellow vest inscribed with lions and griffins. A tall yellow hat with a flower pattern completes the costume see Figure 2.

Figure 2: The painted replica of a c490 BCE archer (at the Parthenon in Athens. The original statue came from the Temple of Aphaia on the Greek island of Aegina.

Why does he look like he does?

Susanne Ebbinghaus, the George M.A. Hanfmann Curator of Ancient Art, suggests the archer probably represents Paris. It was Paris who started the Trojan War by running off with Helen, the wife of King Menelaus of Sparta. Paris later killed the hero Achilles by firing an arrow through his heel.

Ebbinghaus explained that the Greeks of the Classical period often represented the Trojans as Persians, whose armies they had successfully repelled in the early 5th century BCE. The Persian warriors were generally shown as exotic and a bit overdressed compared with the manly, and largely naked, Greeks.

Why so much colour?

On many temples and buildings in Ancient Greece there were many sculptures with much detail. If the sculptures were white the detail would have been indistinct. Colour, and the contrasts of colour, would allow people looking up at the sculptures to determine the detail. Brinkmanns’ study of sculpture from the ’Treasury of the Siphnians’ (c525 BCE) has shown that, not only does colour emphasise the detail on the figures, but inscribed on the wall behind them was the name of the character, allowing viewers to identify both the characters and the drama.

In 2003 the Brinkmanns unveiled their efforts at the Glyptothek museum in Munich, and since then the exhibition has travelled from Munich to Amsterdam, Copenhagen and Rome, and has been received with much interest.

The British Museum has also carried out similar research using a red light shone onto the statue’s surface. In this work they have found Egyptian blue painted on to some statues to colour them. When subjected to strong red light Egyptian Blue gives off infrared light. This is called luminescence. It cannot be seen by the naked eye but it can be recorded using a device sensitive to infrared light, such as a night vision camera.