Teacher fellow Kristy Turner considers what qualifications science teachers need to be effective

‘Those who can, do; those who can’t, teach.’

We have George Bernard Shaw to blame for this phrase. It has haunted teachers since he wrote it in 1903. And it comes into play in every iteration in the cycle of debate about the future of teaching. In the most recent iterations, many have suggested the profession needs upgrading. Perhaps by requiring all teachers to have a master’s degree to qualify.

Those who can, do; those who can’t, teach.’ We have George Bernard Shaw to blame for this phrase. It has haunted teachers since he wrote it in 1903. And it comes into play in every iteration in the cycle of debate about the future of teaching. In the most recent iterations, many have suggested the profession needs upgrading. Perhaps by requiring all teachers to have a master’s degree to qualify.

I don’t agree.

What is a profession?

Teaching fulfils the definition of a profession: ‘a paid occupation, especially one that involves prolonged training and a formal qualification’. As a minimum, a qualified chemistry teacher in England must have a degree (three years) and some form of training or assessment towards the award of qualified teacher status (QTS). Scotland requires a degree in education and chemistry or an undergraduate degree in chemistry followed by a one-year diploma in education. In the sciences it’s common for teachers to have master’s qualifications like MSci or MChem, and PhD qualified teachers are much more common in all types of schools than they were 20 years ago.

I am not convinced a master’s degree would be any guarantee of a more knowledgeable teacher

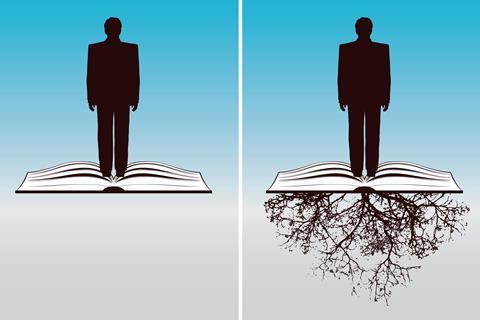

Alternatively, teaching is often regarded as a craft with training almost akin to an apprenticeship. A good proportion of teacher training is learning from peers and through lived experiences in the classroom. However, a craft is defined as ‘an art, trade, or occupation requiring special skill, especially manual skill’ and while there are intensely practical aspects of teaching, it is an intellectual rather than manual endeavour.

Securing subject knowledge

In England, chemistry is a shortage subject for teacher training and classed as a priority subject in Scotland. Requiring a master’s degree would further diminish the potential pool of applicants, potentially depriving more students of a specialist chemistry teacher. However, I am not dismissing the importance of knowledge, particularly subject knowledge. Without good subject knowledge everything else is harder. It is difficult to concentrate on behaviour management, the logistics of practical work, crafting explanations and differentiation when you’re unsure of the subject matter you’re delivering.

It is time to admit that the patchwork of subject knowledge enhancement and courses for non-specialists is a sticking plaster at best

I am not convinced a master’s degree would be any guarantee of a more knowledgeable teacher. If we’re all completely honest the knowledge gained from an undergraduate or postgraduate chemistry degree isn’t commonly used in the classroom. When I first began teaching, what helped me most was my A-level notes, and the automaticity in that knowledge I had gained from studying for those exams. However, what my degree did give me was a certain amount of future-proofing. When I did my A-levels we only studied 1H NMR and kinetics didn’t include the Arrhenius equation. These came onto the A-level specification a few years after I started teaching and my degree equipped me well to deal with those changes. I was able to quickly revisit that knowledge and apply it to the specification.

This also applies to the pushing down of previously AS-level content into GCSE. In recent years difficult concepts like equilibrium, electrochemistry and enthalpy change have been introduced or expanded in the 14–16 curriculum. Ideally a teacher would have a qualification above the one they’re teaching, to future-proof their teaching and add that security of knowledge that makes everything easier.

Want more?

Enjoying this article? Want to read more like it? Make sure you’re subscribed to our email alert.

Specialist or non-specialist?

In the sciences one of the biggest issues that could be considered to be undermining our professional status is the use of non-specialist teachers. In England, anyone with QTS is legally qualified to teach any subject (I once taught French). This gives schools a lot more flexibility with their timetables and is especially useful in covering up shortages. I think it is time to admit that the patchwork of subject knowledge enhancement and courses for non-specialists is a sticking plaster at best. In Scotland a chemistry teacher friend of mine wanted to add physics to their teaching subjects. To be able to teach this to 14–16 year olds they were required to take some undergraduate modules by distance learning, but in England, I would just be expected to teach it, despite not having a qualification above GCSE myself.

Criticism of teachers often has its foundations in poor experiences. The chemistry teacher who is remembered for not being able to do the questions or not being able to control the class. Perhaps instead of a master’s degree, we should stick with our minimum requirements but consider adding an accreditation of subject knowledge with an appropriate examination every few years? Other professions continue to take professional exams; teaching might be considered unusual for not doing. Maybe I should start brushing up on my French again in anticipation!

No comments yet