Watch this

Watch the video and download the technician notes from the Education in Chemistry website: rsc.li/2psZH7u

Cracking long chain hydrocarbons into shorter alkanes and alkenes is a staple of the classroom. But if undertaken using traditional methods, this practical can lead to the dreaded ‘suck-back’ – should students heat for too long or forget to remove the delivery tube from the water at the end of the experiment.

For some time now I have been using the microscale method championed by Bob Worley at CLEAPSS to get around this issue (experiment PP061 for CLEAPSS members). However, I have still found on occasion that students have been disappointed by the results or haven’t always seen exactly what I intended. The exact nature of the starting hydrocarbon and the heating position both play roles in getting optimum results. As such, it’s always handy to be able to have a supply of product alkenes on hand to demonstrate. Using a small modification to the PP061 technique, we can collect enough gaseous alkene, either during the lesson or in advance, to have on standby and ensure the desired learning goals are met.

Kit

- Two 60 cm3 plastic syringes

- Heavy or medicinal paraffin oil (also known as mineral oil) or propan-2-ol (highly flammable), approx. 0.5 cm3

- Silicone tubing

- Aluminium oxide powder

- Glass Pasteur pipette

- Clamp stand with two clamps

- 0.002 M acidified potassium manganate(VII) solution, approx. 1 cm3

- 0.002 M bromine solution, approx. 1 cm3

- Small sample vials

- Sticky tack or two, 3-way Luer lock stopcocks

Choosing your substrate

CLEAPSS members should consult PP061 Microscale Cracking of Liquid Paraffin. If you wish to undertake a cracking reaction, ensure you use either heavy or medicinal paraffin oil, also known as mineral oil – the viscosity is reminiscent of glycerol. Some lighter, less-viscous mixtures, also labelled paraffin, give poor results. The paraffin, once cracked, will generate a gas mixture containing 50–60% alkenes.

If you want a purer alkene mixture in your gaseous product, you can dehydrate propan-2-ol using an almost identical set-up to generate propene.

Preparation

The Pasteur pipette can be converted into a microscale test tube by sealing the thin end in a Bunsen. For best results, break off the last few centimetres before sealing. This helps to avoid the thinnest section melting too quickly and bending, leading to a thin, weak seal.

Holding the tube vertically, drop around 0.5 cm3 of substrate oil into the base, with just enough mineral wool to absorb the liquid. This can be pushed into place with a microspatula or a wooden splint trimmed to fit. Drop a microspatula-load of aluminium oxide into the tube. For paraffin cracking this can be placed up against the mineral wool, but for propan-2-ol dehydration results are better when the heat is focused more on the catalyst than the wool: hold the tube level and tap gently to spread the powder out over 2–3 cm.

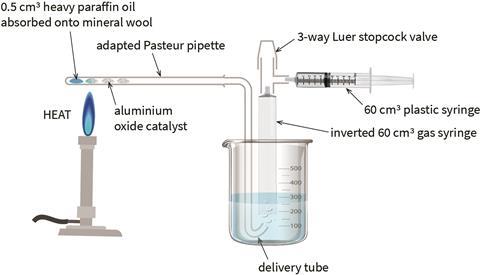

Use silicone tubing to connect the pipette to a delivery tube from which the gaseous products can be collected by downward displacement of water in a 60 cm3 syringe body (see diagram). Water can be drawn up into the syringe by another syringe through a 3-way Luer lock stopcock (alternatively you can use a two-way, Hoffman clamp or sticky tack).

In front of the class

Use an ethanol spirit burner for heating. This will burn hot enough to initiate the reaction, without melting the pipette. For best results in paraffin cracking, focus the flame where the mineral wool and catalyst meet. For dehydrating propan-2-ol, focus the flame on the catalyst 1–2 cm away from the mineral wool.

Almost immediately, the catalyst darkens as carbon deposits on the surface. The first few cubic centimetresof gas, likely to consist mostly of expanded air, can be drawn up into the second syringe and expelled before continuing to collect the products. Over the next 10–15 minutes, the syringe will fill with gas. With paraffin, a viscous, dark-coloured mixture of hydrocarbons will collect in the pipette beyond the catalyst; with propan-2-ol, droplets of water and unreacted alcohol will condense on the sides.

Testing the product

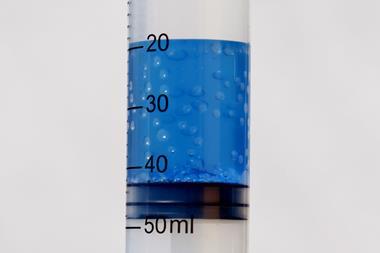

The gaseous products can be drawn up through the 3-way valve into other syringes for testing. Bubble a few cubic centimetres of gas into 1 cm3 of 0.002 M acidified potassium manganate(VII) solution (CLEAPSS members see recipe RB073) or 0.002 M bromine solution (CLEAPSS recipe RB017) in a small sample vial. Close the lid and shake – within a few seconds the solution will decolourise.

By attaching a new Pasteur pipette to the gas syringe via some silicone tubing, you can light the end as you expel the gas for a flamethrower effect similar to the phosphorus flamethrower demonstration. The products of paraffin cracking will give a slightly smoky flame, while the propene from the propan-2-ol will give a very smoky flame.

Health and safety and disposal

- See CLEAPSS recipe PP061.

- Wear eye protection.

- All syringes and silicone tubing can be kept for reuse.

- Dispose of the Pasteur pipette in a broken glass/sharps bin.

- The product solution from the bromine water and acidified potassium manganate(VII) tests can be washed down the sink.

Declan Fleming

Next issue, find out what to do with the alkenes.

Downloads

Technician notes

Word, Size 67.23 kbTechnician notes

PDF, Size 0.35 mb

No comments yet