Five teacher-tested approaches to build students’ basic understanding of acids, alkalis and indicators

Neutralisation and pH are engaging topics for 11–14 learners, with plenty of opportunities for practical work. As there are so many resources available, it can sometimes be difficult to curate the right balance of support and challenge. Use these five tips to reflect on your current teaching activities and explore new ways to grab and maintain student interest.

1. Avoid a watered-down 14–16 approach

The pressure on teaching time can tempt teachers to tweak content for school leaving qualifications. However, 11–14 students have very different needs from older learners. Younger students are making the transition from primary school learning, and neutralisation is often one of the first topics where they experience real chemistry. Spend time laying strong foundations of knowledge by covering key definitions and offering a variety of practical work and contexts to build confident and engaged learners.

2. Choose language carefully

Older resources often label the pH scale with terms like strong acid and weak acid. While not completely incorrect, this ignores the contribution of dilution to pH. As our understanding of misconceptions has improved, more modern resources now describe pH in terms of substances being more or less acidic, avoiding arbitrary divisions on the scale. Use resources like Best Evidence Science Teaching – Substances and properties to help learners explore this idea.

3. Spot the difference: indicators, pH and neutralisation

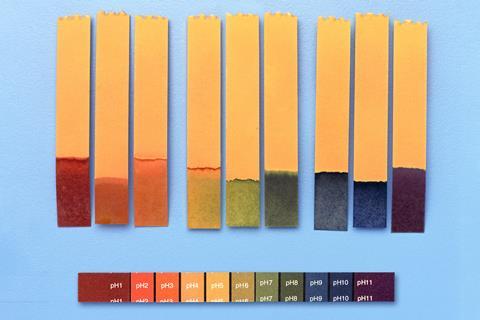

Many resources for this age range focus heavily on universal indicator, which can lead students to rely on it too much in explanations – such as assuming everything green is pH 7. Make use of the freedom within the 11–14 curriculum and show students a range of indicators, both natural and synthetic, including those with just two colours like phenolphthalein and litmus. Using microscale chemistry is a good way to introduce different indicators while managing the cognitive load of using lots of different substances.

You could encourage students to create their own universal indicator by mixing several indicators, such as part two of this microscale experiment. This activity helps them understand how combining different dyes can produce a wide range of colours.

Older resources often label the pH scale with terms like strong acid and weak acid. While not completely incorrect, this ignores the contribution of dilution to pH. As our understanding of misconceptions has improved, more modern resources now describe pH in terms of substances being more or less acidic, avoiding arbitrary divisions on the scale. Use resources like Best Evidence Science Teaching – Substances and properties to help learners explore this idea (bit.ly/3TpmDPD).

3. Finding the right shade: indicators, pH and neutralisation

Many resources for this age range focus heavily on universal indicator, which can lead students to rely on it too much in explanations – such as assuming everything green is pH 7. Make use of the freedom within the 11–14 curriculum and show students a range of indicators, both natural and synthetic, including those with just two colours like phenolphthalein and litmus. Using microscale chemistry is a good way to introduce different indicators while managing the cognitive load of using lots of different substances (rsc.li/3h5pYzr).

You could encourage students to create their own universal indicator by mixing several indicators, such as part two of the ’Universal indicator microscale’ (rsc.li/3U0hcqp). This activity helps them understand how combining different dyes can produce a wide range of colours.

At this point it is worth exploring pH probes, temperature changes and other techniques for measuring neutralisation. It is also a good opportunity to discuss the relative merits of each method and explain why scientists choose different techniques and equipment for different experiments.

4. Let experiments give the ‘wrong’ results

So often in school chemistry the experimental results prove the hypothesis, put simply, they give the results the students (and teachers) expect. Break this pattern with an engaging neutralisation focused experiment, such as Why do nettles sting? from Science Plants for Schools. In this experiment, learners test the hypothesis that dock leaves neutralise nettle stings by using universal indicator on leaf extracts. In practice, dock leaves usually test around pH 1–2, and nettle stings vary between pH 4 and neutral, depending on where they are in their growth cycle – so students do not prove the hypothesis. I always find students are really engaged with this practical, and it provides a good stimulus for rich discussion about neutralisation.

So often in school chemistry the experimental results prove the hypothesis, put simply, they give the results the students (and teachers) expect. Break this pattern with an engaging neutralisation focused experiment, such as ’Why do nettles sting?’ from Science Plants for Schools (bit.ly/4nwPpvm). In this experiment, learners test the hypothesis that dock leaves neutralise nettle stings by using universal indicator on leaf extracts. In practice, dock leaves usually test around pH 1–2, and nettle stings vary between pH 4 and neutral, depending on where they are in their growth cycle – so students do not prove the hypothesis. I always find students are really engaged with this practical, and it provides a good stimulus for rich discussion about neutralisation.

5. Plan mini inquiries with everyday contexts

Learners love answering scientific questions, and this topic offers great opportunities for inquiry once they have grasped the key ideas. Inquiry activities are not intended to teach students the theory aspects of chemistry, instead they help them practise skills like choosing appropriate apparatus, identifying control variables, taking measurements, making observations and forming conclusions.

Neutralisation offers many real-world connections. For example, you could do a mini project on antacid remedies. Give students three types of antacid and challenge them to design an experiment to decide which one works best. I tend to use a popular brand, a supermarket brand and some calcium carbonate from the chemical store, which we call school antacid. You can then encourage students to write a lab report on their investigation, supporting the development of their literacy and scientific writing skills alongside their practical expertise.

Bringing it all together

With the right mix of practical work, clear language and authentic inquiry, you can turn neutralisation and pH into one of the most memorable topics for 11–14 students. By inspiring curiosity now, you lay the foundations for confident, capable chemists in the years to come.

More resources

- Use these evidence-based teaching tips to encourage students to explore PhET simulations – including acid–base solutions and pH scale – independently or in small groups.

- Compare the sugar content and pH of a range of fizzy drinks in your class, science club or as part of an activity day.

- Make acids, bases and indicators accessible to all learners with advice for adapting lessons for those with motor or visual difficulties.

- Investigate the basicity of toothpastes and give context to neutralisation reactions with this article and resource.

- Link pH to careers, such as Beth’s role as a chemistry engineer. She monitors the water quality at a nuclear power plant and tests the pH of water samples.

Kristy Turner

1 Reader's comment