Space out learning to build and reinforce memory

One definition of learning states that ‘if nothing has changed in long-term memory then nothing has been learned’.

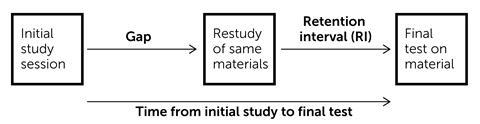

How can we make sure that the students truly learn, rather than merely experience the curriculum? A big answer to this question can be found in revisiting knowledge after a gap. This is called spacing.

Spacing works because, after a gap, students have to work harder to retrieve knowledge from memory. This effort means they are more likely to remember the information over the long-term.

What could spacing look like in a science classroom?

Employing spacing doesn’t have to mean ripping up your curriculum plan and starting again. One method would be to introduce dedicated spacing lessons. Topic 1 is completed. Topic 2 has started, but after a gap, a lesson (or lesson section) revisits content from topic 1. Spacing lessons are not about reteaching information. Rather they are opportunities for students to retrieve previously learned information after a gap. You can use spacing grids to give pupils retrieval cues to help with this ‘desirable difficulty’.

Haven’t got the curriculum time to give up lesson time to previously taught topics? Introduce ‘lag’ homeworks instead, which are set after a gap, rather than straight after finishing a topic. Students will find them more difficult, so you might meet some resistance from them. However, hold your nerve, as they’ll be more beneficial for long-term retention.

7 simple rules to boost science teaching

Click to expand and explore the rules

Build on the ideas that pupils bring to lessons

Help pupils direct their own learning

Use models to support understanding

Support pupils to retain and retrieve knowledge

- Pay attention to cognitive load—structure tasks to limit the amount of new information pupils need to process

- Revisit knowledge after a gap to help pupils retain it in their long-term memory

- Provide opportunities for pupils to retrieve the knowledge that they have previously learnt

- Encourage pupils to elaborate on what they have learnt

Use practical work purposefully and as part of a learning sequence

Develop scientific vocabulary and support pupils to read and write about science

Use structured feedback to move on pupils’ thinking

Lesson starters are another efficient way to implement spacing, and at its simplest, you could ask a question from last lesson, one from last week and revisit something from last term. I use Adam Boxer’s Retrieval roulette to select three questions on my current topic and three randomly selected questions from previous topics at the start of my lessons.

You can also distribute practice of procedures and applying concepts, such as balancing equations, writing ionic formulas and mass calculations. Once these have been taught, you can leave a gap before setting different variations of them as lesson starters throughout the year.

This can be neutral in terms of curriculum time: if you usually spend four lessons teaching and practising mass calculations, reduce this to two lessons, and then revisit them after a gap. The two lessons you ‘saved’ are now distributed across the rest of the year.

So how long should the gap be between initial study and the revisit? The optimum moment to revisit content is just as it is on the verge of being forgotten, which sounds simple, right? This gap gives enough time for recall to be effortful but without it being so long that pupils can’t recall anything.

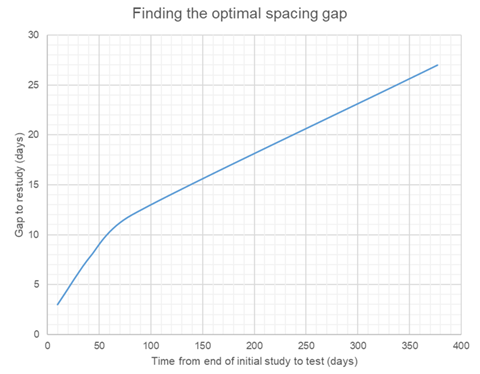

According to by Cepeda et al, the size of the optimal gap depends on the length of time you have until the final test after restudying it (the retention interval). Interestingly, the ratio between the optimal spacing gap and the retention interval changes, depending on how long there is before the final test.

I produced this graph to try to determine what the optimal spacing gap might be for any known length of time from initial study to final test, based on this research:

If you have 260 days left until the exam after finishing a topic, you should revisit the topic after a gap of 21 days, leaving a retention interval of 239 days (before the final exam). This may seem an awfully long time to retain the information, but, if you chose a spacing gap of 100 days instead (which reduces the retention interval to 160 days), students are more likely to have forgotten everything after that initial gap of 100 days, and you might have to reteach the entire topic.

Download the optimal spacing gap calculator (as MS Excel).

My tip would be to use the spacing graph to determine how long to wait before a spacing lesson or lag homework, and then minimise further forgetting by using regular lesson starters to revisit the content. You may be surprised by just how much content they can recall.

This article is part of the series 7 simple rules for science teaching, developed in response to the EEF’s Improving secondary science guidance. It supports rule 4b, Revisit knowledge after a gap to help pupils retain it in their long-term memory.

Downloads

Spacing grid

Word, Size 0.86 mbSpacing grid

PDF, Size 0.18 mbSpacing guide

Word, Size 91.87 kbSpacing guide

PDF, Size 73.55 kbOptimal spacing gap calculator

Excel, Size 53.37 kb

No comments yet